If you recall from the second episode, Mr. Clifford fires a shot at other academic subjects, saying Economics is the greatest of all time. Adriene chimes in with “Take that, Physics!”

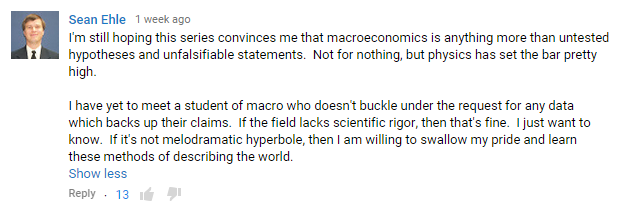

As I was perusing the comment section, I expected to see some rebuttal from a physics student, and I was not let down:

Mr. Ehle here takes some swings back at the field of economics here, and there’s a lot of truth to what he’s saying. However, I think his major frustration comes from when he hears people treat economics as a natural science, instead of a social science.

A natural science (like Physics) uses empirical evidence and the scientific method to prove things. The repeatability of empirical tests is necessary for a conclusion to be deemed valid (for example, water will always freeze at 0ºC, no matter how many times you repeat it).

Unfortunately, the economy deals with so many actors making billions of independent decisions every day, so it would be impossible to create even two identical economic situations to confirm a theory. Economics does not have the advantages of physics where you can create a sterile laboratory environment to prove a hypothesis. Trust me, all economists wish this were the case.

Instead, economics is a social science, the study of humans interacting. Like sociology or political science, there is not a provable “right answer” that scientists can find from researching in a lab; there are only arguments based on theories that will predict what will happen.

However, some social scientists use positivist methods (using data and attempting the scientific method) to try to prove the correct theory. When you hear people say “The Great Depression proved…” or “The 2008 Financial Crisis proved…”, they are using real examples to suggest that scientifically, a particular economic theory is true.

The problem is that almost every economic school of thought can look at a global event and use it to suggest that their theory is true. Let’s take the 2008 financial crisis for example:

Keynesians: The financial crisis proves that the Federal Reserve was setting interest rates too high, since this caused the crash.

Austrians: The financial crisis proves that the Federal Reserve setting rates at all hurts the economy, since this caused the crash.

Marxists: The financial crisis proves that private ownership of the means of production hurts the economy, since this caused the crash.

Everyone can declare themselves the winner, but in the end it doesn’t prove anything.

Mr. Ehle is a hard scientist. He wants data and falsifiable hypotheses and the scientific method to back up claims. He wants to learn the facts about Macroeconomics. Unfortunately, Economics does not work like Physics because it is an entirely different field.

Besides, there is not an actual “greatest subject of all time.” That’s like asking for “the greatest ice cream flavor of all time.”