We’re back for part 2, and we’re just going to jump right in. Here’s the episode if you missed it:

Income and Education

In the last thirty years in the US, the number of college-educated people living in poverty has doubled from 3% to 6%, which is bad! And then consider that during the same period of time, the number of people living in poverty with a high school degree has risen from 6% to a whopping 22%.

Crash Course jumps from discussing the causes of income inequality (see part 1) to the statistical results. I assume this is to imply that technology is widening the income gap so fast that even college graduates are living in poverty.

These numbers are designed to be shocking, and they are. Aren’t schools supposed to give students skills to be successful in real life? And shouldn’t colleges do this to a greater extent, considering students are spending tens of thousands of dollars on it?

If you’ve been to college (or high school for that matter) in the past 10 years, you already know the answer to this: High Schools and Colleges, with some exceptions, are not teaching students the skills they need to survive in the modern economy. Crash Course implicitly blames the number of high school and college graduates in poverty on technology (and other causes they cite which we’ll also get to), while there is no responsibility placed on the failings of these educational institutions.

Over the last fifty years, the salary of college graduates has continued to grow while, after adjusting for inflation, high school graduates’ incomes have actually dropped. It’s a good reason to stay in school!

Crash Course’s argument here implies that going to college will give you steady salary growth because college classes give you the skills to get a higher paying job.

This (again with some exceptions) is not necessarily true. High-paying employers might discriminate against those who haven’t graduated from college, which would also explain the statistics. Many employers see a college degree one of the few ways to judge a candidates ability, since they often shy away from real skills-testing for job applicant since it might be considered an illegal form of discrimination.

This is not to say that someone couldn’t learn marketable skills in college. There are many areas (engineering and computer science come to mind) which actually give students the skills they need for the job market. It’s no surprise that these majors are also the highest paying for college graduates. But the majority of college students do not choose these skills-based majors.

Other Causes of the Income Gap

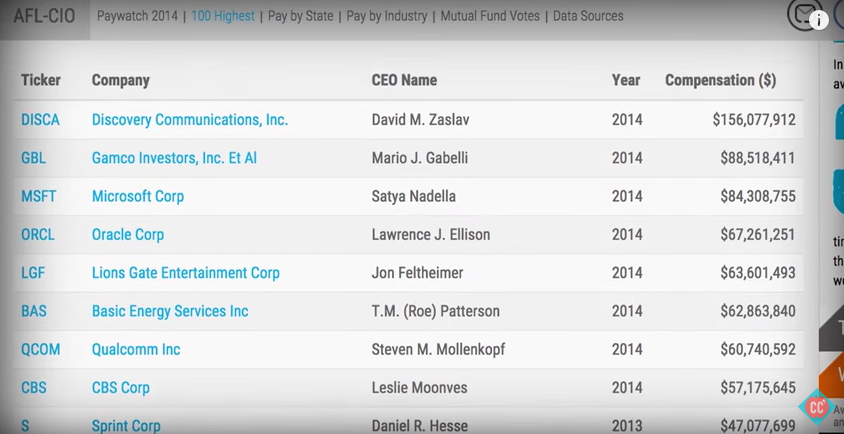

There are other reasons the income gap is widening. The reduced influence of unions, tax policies that favor the wealthy, and the fact that somehow it’s okay for CEOs to make salaries many, many times greater than those of their employees.

Let’s look at each of these in turn:

Unions

Unions, by themselves, are collective bargaining groups for employees that generally demand higher wages from the employer. Originally, they served as a centralized mouthpiece for a large group of workers whose individual voices might not be heard. Their greatest power is the threat of striking if their needs are not met.

In economic theory, unions would help the employer and employees identify the market rate (what the employer is willing to pay and the employees are willing to work for), but it wouldn’t necessarily reduce income inequality. Let me give you two simplified examples:

In scenario 1 there is a company with 10 employees and 1 employer. Employees demand a $1/hour raise or they will strike, and the employer obliges, taking the money from either his own salary (which is rare) or from investor equity. The workers are paid more and there is less income inequality between the employees and employer.

In scenario 2, the workers demand $5/hour more. The company cannot afford this price and remain profitable, so they invest in machinery that will reduce the number of employees needed to 3. The remaining employees might get that $5/hour raise, or the employer might look outside of the union for employees, since it’s now easier to fill the fewer positions available. In scenario two, 7 or more employees are now being paid $0/hour, which widens the income gap.

Unions today, due to abundant legislation related to them, are not the unions of economic theory, and they if they were, they do not necessarily narrow income inequality. Although people might show you a graph of union membership next to a graph of income inequality, one can only speculate that this correlation equals causation.

Tax Policies That Favor the Wealthy

As Mr. Clifford points out later in the video, the United States has a progressive tax system, meaning that the rich pay a greater share of their income above a certain level to taxes. Occasionally, the rich may receive a tax cut. For example, the Bush Tax Cuts lowered the taxes on income over 400k from 39.6% to 35%. In this case, Mr. Clifford is 100% correct, since higher taxes on the rich (absent everything else) does reduce income inequality as a whole.

“Somehow It’s Okay for CEOs to Make a Lot More Money Than Employees”

How about the framing of this sentence? It may not seem “okay” for someone to make more money than someone else, but as economists, the Crash Course hosts should know that wages are not decided by comparing them to other people in the company. We’ve talked about this before on this blog, but wages are decided by the amount of value you produce to the company (as a wage ceiling), as well as how much the employer (in this case the board of directors) and the prospective CEO negotiate for.

I am incredibly surprised that Crash Course implicitly argues that it’s not okay for two people to negotiate a salary irrespective of two other people negotiating a salary for a completely different position in the same company. How did this script make it passed the editors on Crash Course? Isn’t someone there an economist?

I think Mr. Clifford gets it, since later in the video he says:

When different jobs have different incomes, people have incentive to become a doctor or an entrepreneur or a YouTube star – you know, the jobs society really values.

This doesn’t really talk about how wages are determined, but I’ll take it.

Wow guys. There is still a lot more to say, so we’re going to have to make this a three-parter. Thanks for reading and look forward to part three soon (Sunday hopefully)!

Don’t forget to join our newsletter and our facebook group!