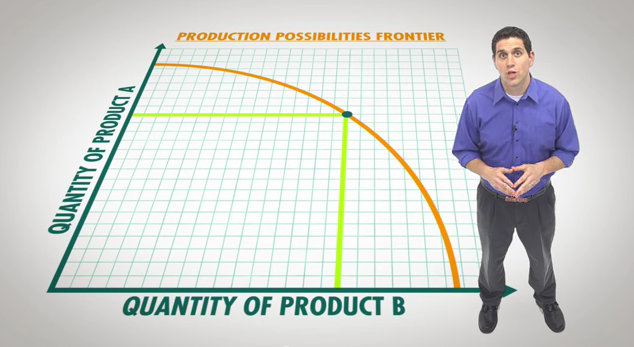

In the first two-thirds of the fourth episode of Crash Course Economics, the hosts explained that supply and demand do the best job of sending signals to consumers and businesses on how much people want something and how much of it there is. The hosts use the examples of strawberries and oil to communicate how these ideas work in real life.

The Fire Department

It seems like the hosts love how markets almost-magically satisfy consumer demand, but only to an extent:

So markets and supply and demand are awesome. But sometimes, they’re not awesome. For example, we don’t want to use the market approach when it comes to firefighters.

This is a common argument: the market is great to an extent, but there are some things that the market is not good for. Since Crash Course came out strongly against government subsidies of businesses (and did an excellent job of explaining it, in my opinion), I was prepared to hear a thorough explanation of why we should forget what they said before, and favor a completely government-funded service instead of the market. Instead of an explanation, Crash Course gave a doomsday characterization of what a privatized firefighting service would look like:

9-1-1, what’s your emergency?

-My house is on fire! How much do you charge to put it out?

It’ll be $10,000, what’s your credit card number?

-They’re all melted!

This probably goes without saying, but because of the infrequent and catastrophic nature of house fires for a household, a privatized fire department would almost certainly charge as an insurance-based system, not a pay-for-it-when-I-need-it service. People privately purchase the same protection for medical and automotive problems (not to mention damage recovery insurance against floods and even death itself), so why not fires?

Unfortunately, Crash Course’s only argument presented was that a privatized fire department would charge too much for its service, and therefore the market wouldn’t work. Or maybe Crash Course is arguing that business would take advantage of desperate consumers whose houses are burning and charge them an unfair price. Besides laws voiding contracts under duress (which would likely be the case here), Crash Course would do well to remember what they argued just minutes before:

As Crash Course argued earlier in the video, the market could certainly provide a suitable price and system for most (if not all) goods and services, fire department included.

The Organ Market

Crash Course brings up an even bigger subject with the example of buying and selling organs, a practice that is prohibited in the United States. This piece of the video strays a bit from economics and delves more into philosophy and morality:

What about the market for human organs? After all, there’s a huge shortage, and thousands of people die each year waiting for transplants. Should there be a competitive market for human kidneys?

A free marketeer would say “sure, why not? If a donor wants $15,000 more than he wants his other kidney, why stop him?”

Well, ethics. I mean, there are several problems that arise in an unregulated market for human kidneys. First is the moral question: is it fair for a poor person who can’t afford a kidney to die while a rich person lives? Well…no not at all!

Not to be the bearer of bad news, but we already live in a world where rich people survive in situations where poor people do not, including organ donations. Rich people can travel to other countries to get organ transplants, while poor and even middle class people cannot.

The question is: should more people have access to a service, even if not everyone would be able to have access to the service? Should this only apply to organ transplants or all medical services in general? What about in health-related areas like nutrition and safety? Should certain goods and services be prohibited because some can afford them and others cannot?

Another problem results in the law of supply. When there’s an increase in the price of kidneys, there’s an incentive for people to steal and sell kidneys.

First of all, legalizing the sale of kidneys would decrease the price of kidneys, since the current price can only be found at high, black market rates. Second, I imagine that doctors and hospitals would have some standards that would prevent someone from walking into a hospital with a bag of organs to be used for transplants. Hospitals (and if not, governments) would be able to set the standards to prevent stolen organs from entering the legal transplant system.

Currently, you can sell your blood or plasma for money. Is Crash Course concerned that people will steal and sell blood or plasma?

There may be a good argument against the voluntary buying and selling of organs, but I don’t think it’s in this video. If you do have a good argument against it, please drop it in the comments.