It’s been a while, I know. I’m still about 4 episodes behind, but I’m about to start publishing my posts on a fixed schedule to catch up, and so you know when to expect them. Stay tuned for more info in the next post.

As per usual, this episode of Crash Course was a mixed bag of good, bad, and glossed-over economics. I’m going to start with the most egregious mistake:

Military Spending

Getting out of the depression took nearly a decade, and it wasn’t really monetary policy that put an end to it. It was the massive government spending of World War II.

But Adriene! Remember what you said in Episode 1?:

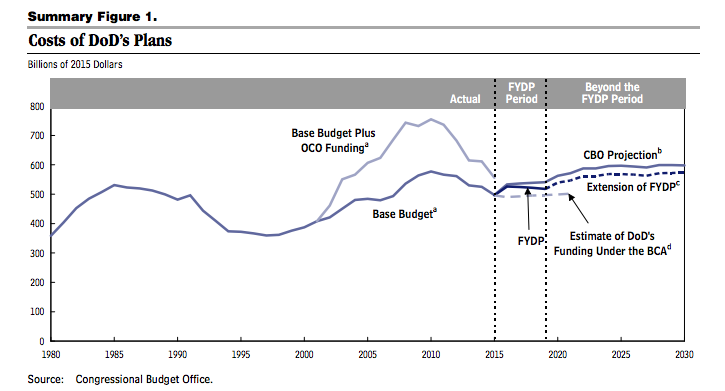

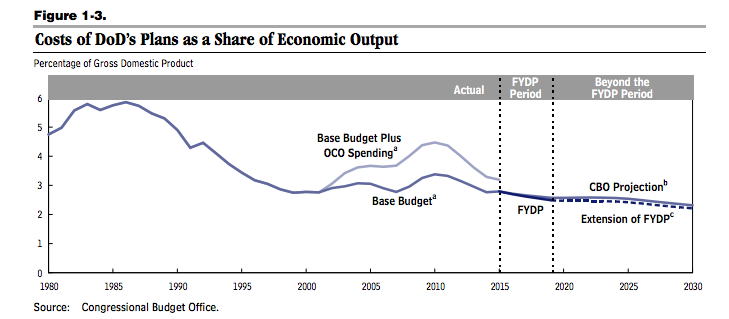

Military spending in the United States is over $600 billion per year. That’s close to what the next top 10 countries spend combined…the opportunity cost of [each] aircraft carrier could be hospitals, schools, and roads.

I realize now that Crash Course believes any and all government spending is good for the economy, including things that do not benefit the public generally. If you remember back to their discussion of opportunity cost in week one, every dollar spent (either by government or private persons) could be spent somewhere else (also either by government or private persons). So why would Crash Course think that military spending can help get the government out of depressions?

In short: Keynesianism. We talked about the show’s Keynesian Presuppositions before, but this makes it clear: Crash Course believes spending is what fuels the economy. When people are not spending, governments need to step in and (tax and) spend for them! If you recall, we critiqued this idea in episode 5, so I won’t go through it again, but in short: saving also fuels the economy.

Monetary Balance

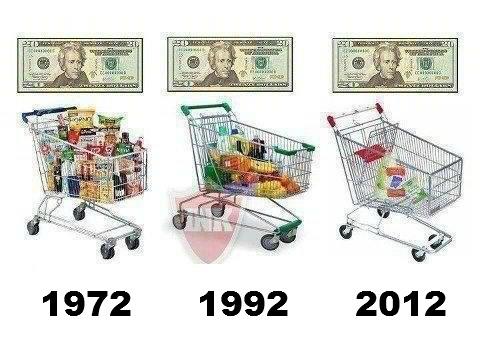

An increase in the money supply can have two effects. It can increase output or increase prices or some combination of the two. Inflation starts when output is pushed to capacity and can’t rise much further, but policymakers continue to increase the money supply. In theory, once output is maximized, the more money you print, them more inflation you’ll get.

This theory, stated as fact here in Crash Course, is one of multiple ideas of how the money supply affects the economy.

First, the “output or price” dichotomy is generally not how most economists think of money printing. All economic schools of thought believe that money printing will always increase prices, but some economists think that the boost to output is worth the pain of rising prices. It’s not an either/or scenario; it’s an “is it worth it” scenario. Sometimes the price inflation doesn’t occur immediately, but as the money circulates, prices will rise.

The Austrian School however, argues that money printing will distort the economy, flooding money into certain areas and creating bubbles, only to eventually crash and do even more harm than if the government had not interfered at all.

Hyperinflation

Crash Course rightly puts some of the blame for hyperinflation on central banks who print money to oblivion, but they also seem to blame consumers:

After a couple of years of doubling prices, people started to expect high inflation, and that changed their behavior. Say you’re planning to buy a new refrigerator, and you expect prices to rise quickly. You buy it as soon as possible before the prices have a chance to change, but with everyone following that logic, dollars start to circulate faster and faster and faster.

Economists call the number of times a dollar is spent per year the velocity of money. When people spend their money as quickly as they get it, that increases velocity, which pushes inflation up even faster.

Consumers do not create inflation (central banks do), but they can speed up or slow down how long it takes for the newly printed money to affect prices. If the central bank printed a bunch of money but kept it out of circulation, prices would not rise, but when that money starts to circulate, then prices rise. Once the new money is out there, it can take a long time or a short time for that to affect prices, but the eventual rise in prices is due to the initial money printing.

But Crash Course seems to think that consumers’ eagerness to spend is what pushes prices up, even if the printing has stopped.

Let’s imagine an economy without a central bank setting interest rates, and instead, interest rates were determined by the market. If something like this were to happen and everyone quickly spent their money as soon as they received it, businesses who wanted large loans would have a very hard time getting them, since money is being spent instead of saved. The most in need of loans would be willing to pay a premium for it, and banks would offer high interest rates to encourage people to save money, so they could lend it out to businesses. People would eventually stop spending as much as they notice that it would be more beneficial to save their money and collect a high interest rate.

Once a central bank enters the picture, interest rates are held artificially below the market rate, encouraging people not to save and for banks to borrow more newly-printed money from the central bank for a low rate.

Later in the video, Crash Course uses the same logic to talk about rapid deflation: consumers’ expectation of lower future prices keeps them from spending and sends prices further down. It’s a much harder argument to make for them, and we’ve already covered this argument in this post.

Stagflation

Crash Course correctly identifies what Stagflation is: when the economy is not improving but prices rise quickly. But when they explain the United States stagflation, they miss a key point:

The US experience Stagflation starting in the 1970’s after a series of supply shocks, including a rise in oil prices, and believe it or not, a die up of Peruvian anchovies, which were important for animal feed and fertilizer.

I’ll pick the “not” option. Natural disasters and supply shocks can have negative (or stagnant) effects on the economy, but these do not cause the inflation part of the stagflation formula. What does this have to do with central bank money printing?

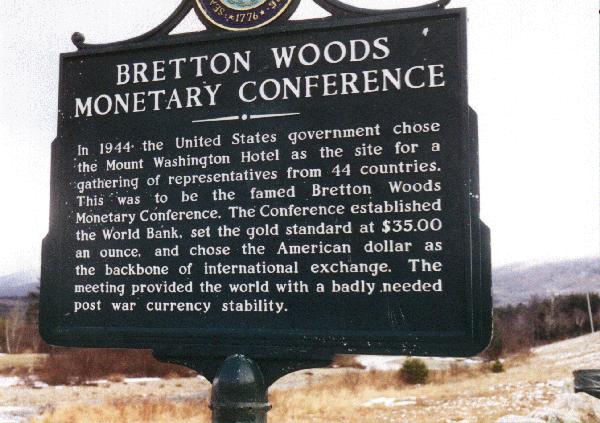

It was very surprising to hear an entire section on Stagflation without mention of the Bretton-Woods System and the United States’ complete removal from the gold standard. That’s almost like talking about the 2008 financial crisis without mentioning FEHA or Fannie Mae.

Bretton-Woods was a monetary system that the United States had from 1944 to 1971. It was a quasi-gold standard, where the government still fixed the price of US dollars to gold. The Bretton-Woods System also establish the US Dollar as a reserve currency, and allowed foreign countries to trade their US dollars for gold at the fixed rate.

Throughout the 1960’s, US money printing made many international countries nervous about the dollar’s viability, and many of them exchanged their US dollars for gold. Eventually, the United States ended its international dollar/gold exchange, thus ending the Bretton Woods system and creating free floating fiat currencies across the globe.

Naturally, the end of the Bretton Woods system caused the US dollar to plummet in value relative to foreign currencies. It became very expensive to import items and for US companies to do business internationally. The resulting strain on international trade caused prices to soar in the United States.

Like what I wrote? Hate it? Drop some feedback in the comments.