We’re back for the second part of Crash Course Economic’s episode on Market Failures, Taxes, and Subsidies. In this post we’ll cover the second half of the video, which talks about externalities, pollution, and the education system. Let’s rock and roll:

Negative Externalities

Remember, sometimes markets misallocate resources because they don’t have the right price signals. There is no better example of this than what economists call externalities. Externalities are situations when there’s an external costs or external benefits that accrue to other people or society as a whole.

Market misallocation of resources is something we covered last week in episode 20, so I won’t go into it here. What Mr. Clifford is trying to say here is that markets don’t take into account negative externalities when pricing a product, since the companies don’t have to pay for these externalities.

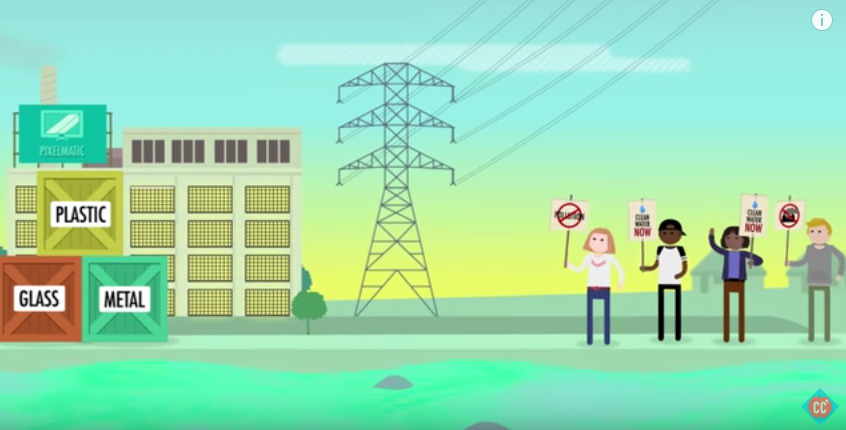

Let’s look at a TV factory that pollutes a river with toxic chemicals. This is definitely a negative externality […] There are also external costs associated with polluting the waterways, like dead fish, contaminated drinking water, and people getting sick […] The free market assumes that all the costs associated with producing TVs are accounted for within the price of those TVs, but, in this case, the market is wrong. The end result is a market failure because the factory is producing too many TVs.

This is a textbook example of a negative externality. An entity is directly responsible for a lot of bad things, but the entity never has to take legal responsibility for it. Something is clearly wrong here, but what’s the solution? Crash Course offers one that’s used most often:

Economists often look to the government to step in and solve the problem. For example, the government could tax the TV factory.

The taxes will increase the cost of producing each TV, and thus reduce the supply and raise the price of each one. This bring the supply and price closer to what Mr. Clifford and many government economists have determined to be the appropriate supply/price for a TV, since according to them, the free market could not do it on its own.

While this solution may bring the supply and price closer to what the real market would be if the TV factory had to account for the negative externalities, it doesn’t clean the river, and it doesn’t incentivize the TV factory to stop polluting the river. In the end, the river is still polluted, but now the government has more money. Is this the trade off economists are looking for?

Instead, some economists suggest, the problem is one of property rights. If someone owned the river or the right to use it, he could sue the factory for violating his property rights. Since rivers are owned by governments (remember tragedy of the commons?), no private individual could sue the factory. The government is satisfied with the taxation solution since it means a new stream of cash flow, but it probably doesn’t mean much to the people who have use the polluted river. But where would the money collected from these taxes go (at least, in theory)? To the positive externalities, of course.

Positive Externalities

More education is great for you. You’ll likely generate more income and it makes you more interesting to talk to at parties. But there are also external benefits of your education. Everyone is actually made better off. With more education you’re more likely be a positive and productive member of society. And if you earn a higher income, that means more tax revenue.

Funding education would, in theory, produce graduates with much greater productive value. This increase in value would be better off for the economy at large, since more wealth is now created. That wealth would also be taxed. If you’ve ever heard someone say that “subsidized education pays for itself,” this is the theory behind it.

Of course, this is assuming that putting money towards any school system is a good return on investment. Considering the extremely high price of college tuition, is each dollar really spent wisely on improving the productive capacity of its students?

If the government didn’t get involved, all education would be provided by private schools that would charge tuition; there might not be enough affordable schools to educate young people. The government funds education because they think that the external benefits, like literate, well-informed, erudite citizens, are so high it’s worth forcing everyone to pay.

Well-informed, erudite citizens. Is that the world we live in? According to the most recent statistics, about a quarter of the United States is functionally illiterate.

Of course, it’s very difficult to speculate about what the market would look like if there were not any public education. The education market as a whole is so heavily influenced by the public school system, economists can only theorize about what low-cost private schooling choices would appear if they were not crowded out by no-cost public schools.

But what economists always ask themselves is “compared to what?” Would people be better off if the government put the money (wherever it comes from) toward education, some other project, or back in the hands of the citizens? That’s very hard to tell, but for spending over $12,000+ on every elementary and secondary school student, would the students would be more literate, well-informed, and erudite if that money went to private tutoring?

Thanks for sticking around for part two of this week’s episode. Please come back every Thursday for a fresh new post on a new episode. And don’t forget to join our newsletter and our facebook group, and comment below!