And we’re back for part two! In this post we’re going to talk about the finer points in episode #8, namely what economists think of “Austerity” and “The Multiplier Effect”

Austerity

Crash Course explains Europe’s response to the 2008 financial crisis as such:

[European countries] were pursuing a policy called Austerity: raising taxes and cutting government spending to reduce debt.

While in the US, Keynesian recessionary policy called for increasing spending and increasing their deficit (and debt), countries in Europe were focusing on reducing their deficits (and debt).

Important distinction: A country’s deficit is the difference between what a government spends and the amount of revenue it takes in. A deficit means that the country has spent more than it has a collected, resulting in more debt at the end of the fiscal year. In other words, a deficit is the yearly rate of increasing debt.

Side note: When people talk about Austerity, they are usually referring more to the reduction in government spending and less about increasing taxes, while both are technically austere.

Crash Course does not stray from the common opinion that Austerity is bad for an economy:

Since 2011, when the US and European policies really started to diverge, the US economy has grown at an average rate of 2.5%, while the Eurozone GDP actually shrank by %1. US unemployment fell to 5.5%, while Eurozone unemployment rose to 12%.

Just the facts here, all of which are true. From here, Crash Course moves on to talk about another subject, which leaves the viewer thinking “well, with these numbers, austerity clearly doesn’t work and Keynesianism does.”

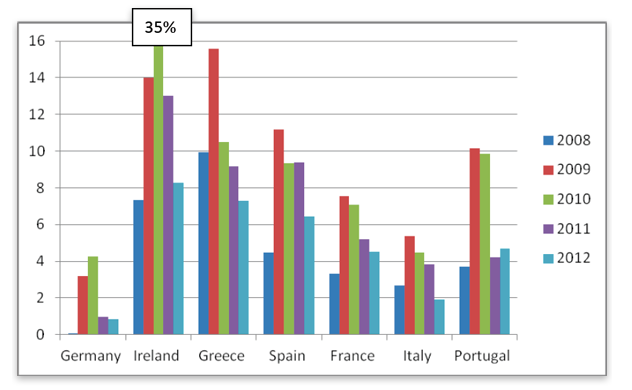

What needs to be mentioned is what European Austerity really entailed. How much did governments reduce their spending, and how much debt did they reduce? Below is a chart of European countries and their deficits (not debt) as a percentage of GDP:

European countries continued to spend more than they took in, resulting in more debt (also known as taxes on future economies) each year. While many countries decreased their deficits, they still continued to increase their debt. Is this really Austerity?

If you compare the resulting budgets (spending and revenue) of the US and Europe following the financial crisis, they don’t look like opposites. Europe is Keynesianism Light, while the US is like Keynesianism Extra.

As I mentioned in the last post, increasing government spending, financed through debt, will benefit the economy in the short-term at the sacrifice of future economies. And free market economists would argue that since you are taking from the private sector and spending in the public sector, that action will necessarily make the economy worse off.

Since both Europe and the United States are spending now what they will need to tax later, it makes sense that the present economy of the bigger spender (the US) would be doing better in the short-term. But to take selected facts and declare “increased government spending = prosperity” would not be showing the full picture.

Multiplier Effect

The multiplier effect theory is often attributed to Keynes (among others), and Crash Course explains how the theory goes:

The idea here is that if the government spends $100, then the highway construction worker who got the money will save $50 and spend $50 on a concert or something. The musician who got that money will save $25 and spend the other $25 and so on. So because of this ripple effect, the initial increase in government spending of $100 might turn out to $175 worth of actual spending in the economy…

Spending on welfare and unemployment seem to give us the most bang for our buck, since people with low incomes spend virtually all of their additional income.

Basically, spending money on the poorest individuals results in a better economy because poor people are more likely to spend that money than save. Spending is good for the economy, and saving is bad.

I mentioned this before, but money that you put in the bank doesn’t just sit there. Banks lend out that money to the people who want it and are willing to pay interest on their loan. Crash Course rests a lot of their economic arguments on the assumption that saving doesn’t improve the economy. In reality, saving, instead of spending, merely shifts money toward capital goods instead of consumer goods. The money gets used either way.

The multiplier effect also rests on another principle:

General cuts to payroll and income taxes seem to have a multiplier of about 1; if the government cuts $100 in taxes, the economy is going to grow by about $100 […] Tax cuts puts money into people’s hands quickly, but that money might get saved rather than spent.

I don’t know if this is true or not, and Crash Course did not explain why someone’s tax savings (or more like, many people’s marginal tax savings) is not likely to be spent, while money toward a salary would be.

Regardless of whether this is true or not, the money would be used whether government takes it from people, or someone puts in the bank and it’s lent out.

Crash Course’s Greatest Moment Yet

Crash Course concludes this episode with a fantastic point:

When people are miserable and unemployed, they want to feel like help is on the way. Doing nothing doesn’t create the kind of confidence that will get consumers and businesses spending again. And it doesn’t get politicians reelected. So it looks like Keynesian policies are here to stay.

For now, I’m going to ignore the claim that recessions are corrected by consumers and businesses “having confidence in spending more.”

The most refreshing part is the reluctant acceptance that, whether or not Keynesian economic policy is correct or not, it is going to be implemented because it gets politicians reelected, and it makes people feel like help is on the way. Nevermind what is effective economic policy, what’s important is that it you believe it’s effective. And why wouldn’t you? Policians (and to some extent, Crash Course) tell you it’s effective!

Like what I wrote? Hate it? Drop some feedback in the comments. Also sign up for the Newsletter (first one is coming soon).