Back again for another week of Crash Course Economics! Aren’t you loving it? We sure are here at Crash Course Criticism.

This week’s episode was, for the most part, a pretty accurate explanation of the roles of markets, and prices versus a planned economy. Crash Course does make a few generalizations, but on the whole, this episode surprised me in a good way with its refutation of common economic arguments on “price gouging” and “predatory pricing.” Let’s get started:

Markets and Efficiency

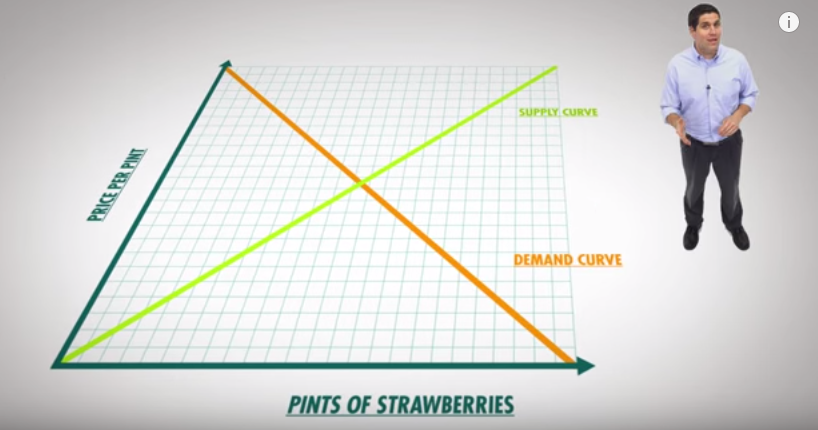

The problem with central planning is that it’s inefficient. Now, when economists talk about efficiency, they’re talking about a couple different types of efficiency.

Crash Course doesn’t beat around the bush when talking about government inefficiency. They don’t tell the audience that governments are usually less efficient, or that there are exceptions to the rule. And while there are articles that claim this not to be true (like here, here, and here), this is an economic truth, and Crash Course does a great job at explaining why:

The first is productive efficiency: the idea that products are being made at their lowest possible cost […] Central planners in general, aren’t that focused on cost. But in the free market an individual business owner has an incentive not to be wasteful because they want to maximize profit.

Governments agencies do not have a “bottom line” to meet, so to speak. They are not worried about the threat of corporate bankruptcy or investors making sure that the organization is making the best decisions. If someone makes a wrong decision about how many widgets to order or the estimated cost of a project, there is unlikely to be the same negative reaction from superiors that would be seen at a private company. And when the employees aren’t incentivized to do the best job or produce the greatest value, the entire organization will naturally be more inefficient than its private counterpart.

The second type of efficiency is called allocative efficiency This means that the things we’re producing are the things that consumers actually want. In other words, our scarce resources are being allocated towards the things we value. Central planners are less likely to be allocatively efficient because they have a harder feedback about what people want.

Customer service and feedback are a big part of any large business. Have you ever complained to Uber about a bad ride experience you had? Uber would usually apologize, refund your ride, and may even give you a discount on future rides. Now have you ever complained to the DMV about a bad customer experience?

Businesses focus on meeting consumer needs because they don’t want to lose you to their competitor. They are incentivized to take care of you, since a satisfied customer will likely continue to do business with that company.

Planned Economies do not pay much attention to the consumer in these areas, since there is no incentive to. If the government controls a sector of the economy, and there is no alternative for consumers, why would they need to take care of the customers? Where else are they going to go?

Prices

Crash Course explained the role of price signals very well with their example of Skinny Jeans:

If people are paying high prices for skinny jeans, it tells producers “Society wants more skinny jeans, start making them.” If no one wants skinny jeans, producers start making something else instead. Here’s another example: tablet computers weren’t really popular until Apple introduced the iPad. After that, boom! The market exploded.

Price signals play an important role of signaling to producers what people want and how much they want it. These signals allow for more competitors to enter the market and compete on quality and price.

The market decides what the price is, and consumers decide if a price is too high by not buying it.

Price Gouging

But what about when companies charge high prices in times of emergency? Aren’t they just trying to maximize profit at the expense of everyone’s well-being? Crash Course deals with the “price gouging” complaint surprisingly well:

[Economists] argue that allowing prices to increase in times of crisis encourages others outside the disaster zone to haul in and sell essential goods. If prices aren’t allowed to increase, then there’s less of an incentive to bring this stuff in. Furthermore, higher prices for things like batteries, sleeping bags, and generators mean that people who don’t really need them won’t buy them, making them more available to people who do.

Using the supply/demand model, an emergency decreases the supply of goods, thus increasing the price. By artificially holding down the price (which many states do with anti-price gouging laws), the supply quickly disappears with no incentive for suppliers to enter the emergency to increase supply. Even with rationing (which anti-price gouging laws must implement to prevent supplies from disappearing), the price will not direct the goods to those who really need them.

Predatory Pricing

Similarly, “predatory pricing” is another complaint that some may have when they think a company’s price of goods is too low.

Side note: I’d like to take a moment to recognize that we live in a world where normal people (not just business competitors) complain about a company’s prices being too low. What a world!

The Predatory Pricing argument is similarly dealt with very well by Crash Course:

[Predatory Pricing] is the idea that a business can drive out competitors by charging lower prices even at a short term loss. Competitors that can’t sustain such low prices will be forced out of the market, giving the surviving businesses market share and the ability to raise prices.

When a business successfully eliminates their competitors by selling products at a loss, they’re eventually gonna need to increase their prices above the market price to make up for those losses. In the short run, consumers would have to pay more. But eventually, other businesses would be attracted by the higher prices and enter the market. The end result is that there’s no guarantee that predatory pricing is worth it in the long run.

Perfectly put by Crash Course. In short, predatory pricing wouldn’t work, and if companies try it, they do so at their own eventual peril.

Regulation

Crash Course makes a very small note on the need for regulation by talking about rat pellets in our wheat:

In the United States, which is often mistaken for a free market economy, it turns out just about everything is regulated. For example, FDA regulations reject any wheat that contains nine milligrams or more rodent excreta pellets and/or pellet fragments per kilogram.

After this remark, the show immediately changes to talking about the market, without ever coming back to this point. If the point here was to show that the United States is not a free market economy, I get it. But if, however, this is meant to show that government regulation is the only way to keep rat poop out of our lunch, well, we’ll have to deal with that when their future episode on regulation in general.

Consumer Choice

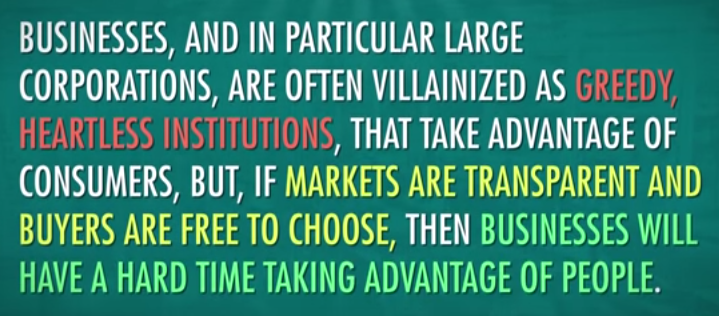

Crash Course finishes the episode with a really nice note on consumer choice and ethical business practices, which I would like to reprint in full:

Here’s the big takeaway: Capitalism, with its system of price signals, is basically crowdfunding. We collectively choose what we want and how we want it made when we spend our money. After all, companies can’t force you to buy their stuff, they have to earn your money. Now if you want to see real changes in the world, don’t just complain that corporations are greedy; expect more from them.

You also need to expect more from ourselves. If you disagree with the way a retailer treats its workers, then don’t buy from them. Even if they do have the lowest prices and convenient delivery options. If we as consumers want our purchases to have a positive impact, it’s on us to seek out companies that try to improve the world. This might mean paying more for the stuff we buy or it might mean buying less stuff. A market based society still has shared social goals. They just don’t come from a central planner.

I thought this was a great note to end on. Markets do the best job at responding to customer needs, but it’s also up the consumers themselves to decide what those needs are. Feel free to boycott businesses you don’t like. Consumer demands is what keeps them in line.

But if you’re the only one who is boycotting Bed, Bath, and Beyond (just an example), maybe that’s because people just don’t care about the cause as much as you do. Instead, try to persuade others in refusing to patronize their business.

Two weeks in a row of excellent (by that, I mean accurate) Crash Course episodes. Can they make it a hat trick? Come back next week to find out!

Don’t forget to join our newsletter and our facebook group, and comment below!