This week Crash Course takes a step in the pro-government direction, despite concluding at the end of this episode that neither markets nor government is “better,” but rather that the two must work together for everyone’s benefit. This episode is such a doozy that it’ll be broken into two parts. Let’s get started:

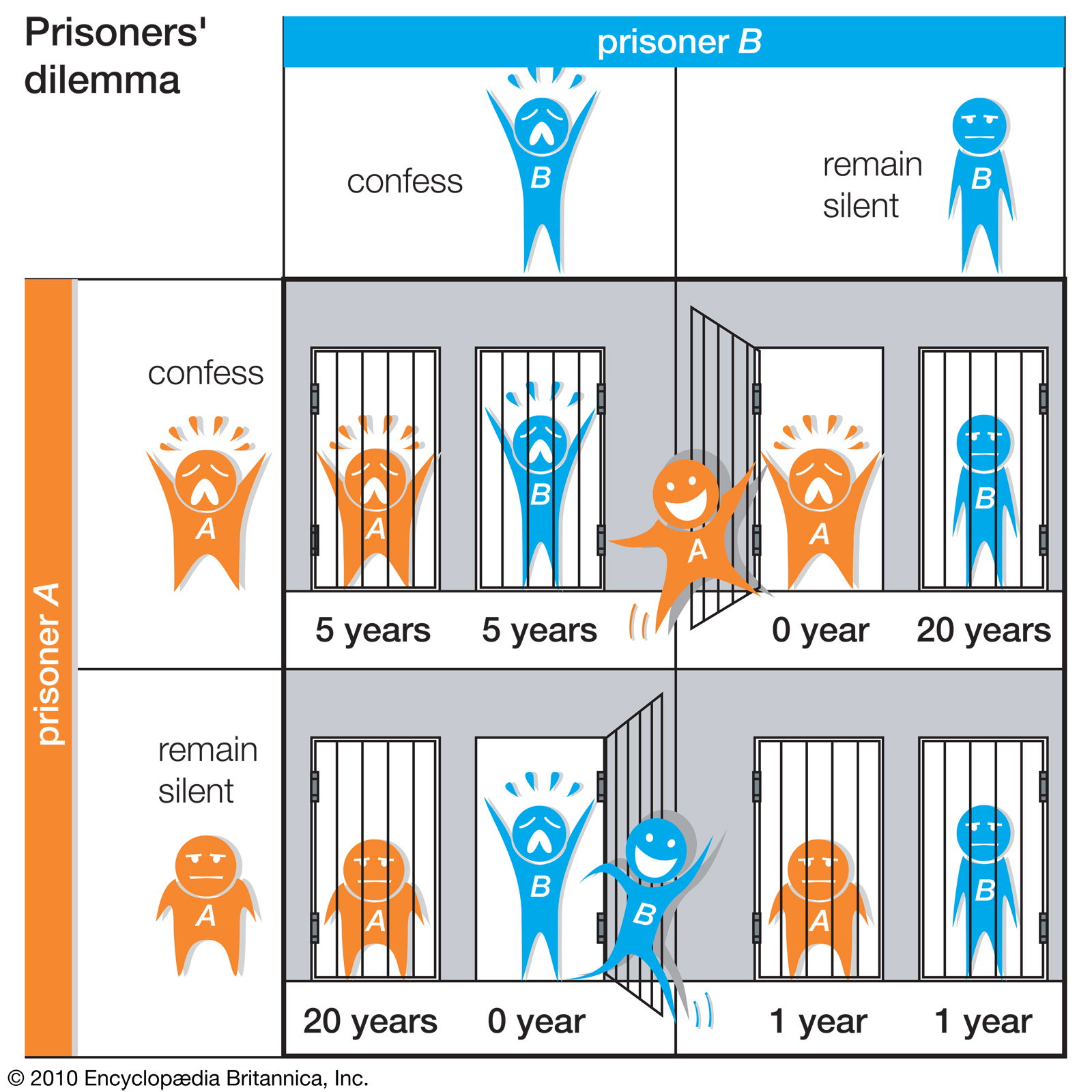

Prisoner’s Dilemma

The episode begins with a variation of the prisoner’s dilemma situation in game theory. In short, the game offers someone a choice between something that will benefit them a lot vs. something that will benefit them a little, but if that person and other people (who are given the same choice) also choose the more beneficial option, then all parties end up with a very bad result.

The [prisoner’s dilemma] question alludes to one of the biggest problems with free markets: sometimes people have a personal incentive to do something that is against the collective interests of the group.

I found this connection pretty attenuated, since this problem doesn’t really have anything to do with free markets. In fact, this problem could be just as easily (or more easily) be connected to the tragedy of the commons than to the free market. We’ll better explain these terms (market failures and the tragedy of the commons) later in this post.

Market Failures

Despite it being so important that it’s named in the title of the episode, the term Market Failures is only briefly defined before moving on. Let’s look at how Crash Course introduces it:

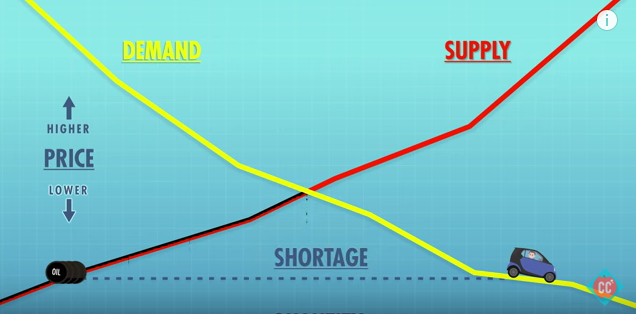

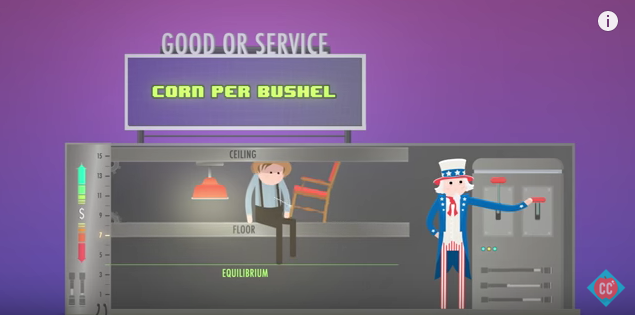

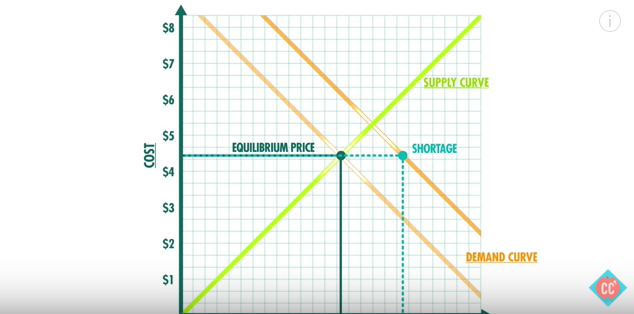

Things that are for our collective well being, like fire protection, schools, and national defense are often funded by the government. When markets alone fail to provide enough of these things, that’s called market failures.

The term “Market Failure” is used to describe when the market does not produce something (or enough of something) to meet consumer demand. Markets are always adjusting to meet consumer demand, but the term Market Failure is usually used for allegedly huge discrepancies between supply and demand.

For example, Crash Course purports that if government fire departments did not exist, then there would not exist any fire protection for people. Since people need fire protection, the government must step in during these Market Failures.

Confusingly, evidence of privately-owned and operated Fire Departments is so abundant, I’m surprised that Crash Course would use this as one of their examples where the market cannot provide. National Defense is a much harder example to argue against, so I’m wondering why Crash Course extrapolated on their weakest example. Of course the market can provide for fire protection services, since it does in many areas for less cost.

Public Goods

Crash Course gives the textbook definition of public goods:

The technical definition of a public good is anything that has two characteristics: non-exclusion and non-rivalry. Non-exclusion is the idea that you can’t exclude people that don’t pay. For example, it’s impossible to limit the benefits of national defense to only people that pay their taxes. People who pay no federal taxes still get the benefit of protection from bombs, and people who pay a lot of federal taxes don’t get extra protection. Non-rivalry is the idea that one person’s consumption of the good doesn’t ruin it for other people. So, public parks are a great example. You can use it today, I can use it tomorrow; it can be shared.

It’s hard to improve upon this definition. One particular area to note, however, is that things like Fire Departments would not be considered public goods, since they are not non-rival. One city cannot adequately provide fire protection services to 50 buildings that are on fire in different locations at the same time.

While the definition of public goods is accurate, some schools of economic thought may have a problem with a common conclusion regarding public goods, which Crash Course gives immediately after defining it:

If a good or service meets these two criteria it’s unlikely that private firms will produce it, no matter how essential it is. Street lights and organizations that track and prevent the spread of diseases are pretty important, and if the government doesn’t step in, we probably won’t get them.

First, while Crash Course (and other economists) argue that it is unlikely the private firms will produce items that fit the definition of public good, there are plenty of examples to the contrary, especially today. Any software or website made available for free or funded by donations (Wikipedia, WinRar, etc.) meet the definition of public good and were created privately.

Additionally, Crash Course’s two examples (street lights and the CDC) might not be the best examples to give. Street lights would fall into the Tragedy of the Commons category (which we’ll get to, I promise), since they are on public property, and there exist plenty of private organizations that track and prevent the spread of diseases.

Tragedy of the Commons

Crash Course next talks about Tragedy of the Commons, one of the most important principles to any free market economist:

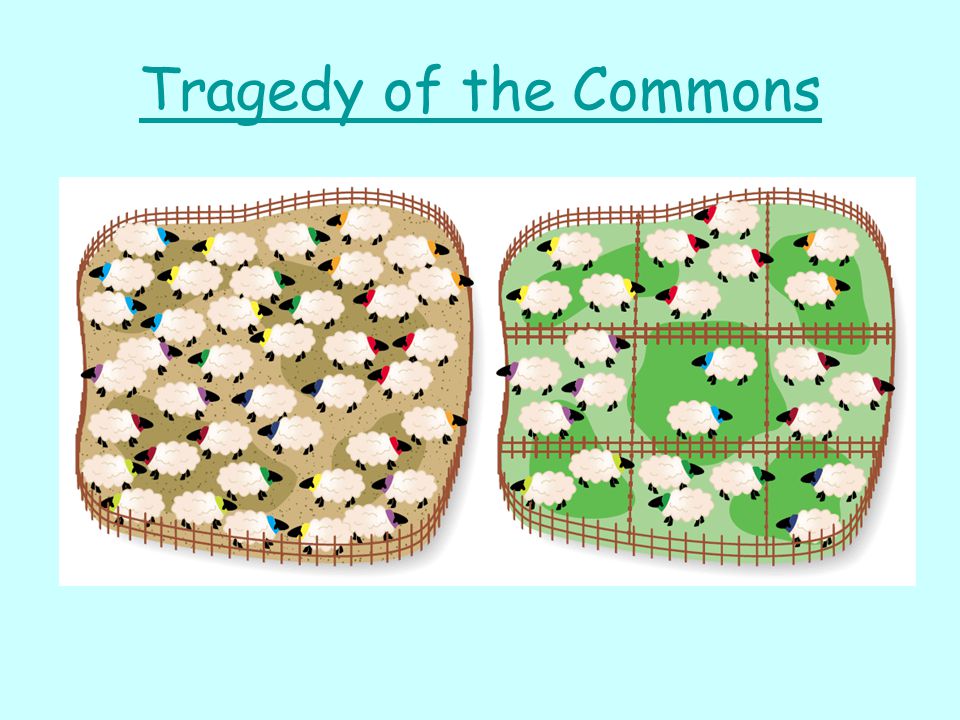

The incentive to do what’s best for you, rather than what’s best for everyone is the root cause of something economists call the Tragedy of the Commons. This is the idea that common goods that everyone has access to are often misused and exploited.

The best visual understanding of The Tragedy of the Commons comes from William Forster Lloyd, whose example is still used to this day (via Wikipedia):

In 1833 the English economist William Forster Lloyd published a pamphlet which included a hypothetical example of over-use of a common resource. This was the situation of cattle herders sharing a common parcel of land on which they are each entitled to let their cows graze, as was the custom in English villages. He postulated that if a herder put more than his allotted number of cattle on the common, overgrazing could result. For each additional animal, a herder could receive additional benefits, but the whole group shared damage to the commons. If all herders made this individually rational economic decision, the common could be depleted or even destroyed, to the detriment of all.[5]

The Tragedy of the Commons is often used as an argument against public ownership of goods and for private property. After all, if you are a farmer and owned your own parcel of land, it’s unlikely that you’ll let it become overgrazed, since that will hurt you in the future. However, the writers at Crash Course see it a different way. To them, Tragedy of the Commons is not a argument for privatization, but rather one for regulation.

The Tragedy of the Commons explains why fish stocks get depleted, the rainforest get cut down, and why endangered species get hunted for their hides or horns […] The problem here is that unregulated markets sometimes don’t produce the outcome that society wants.

As Crash Course will talk about later in the video, there are two ways to look at the solutions to problems such as these: one is a regulatory solution, and the other is a market-based solution.

In general, economists tend to prefer market-based policies.

Despite admitting (and later explaining why) market-based policies are preferred, when talking about examples of Tragedy of the Commons problems, their proposed solution is nonetheless regulatory. Crash Course never explains why they recommended the admittedly less preferable solution.

There’s still a lot to talk about with Crash Course’s analysis of externalities, the education system, and Cap & Trade, so be on the look out for a bonus blog post this Saturday. And as always, you can expect a fresh post every Thursday. Don’t forget to join our newsletter and our facebook group, and comment below!