In this week’s episode of Crash Course Economics, the hosts talk about deficits and debt. This episode might have better scheduled if it were before the videos on Keynesian Macroeconomic Policy, where they talked about deficits and debt, only to define the terms later.

Debt and Spending

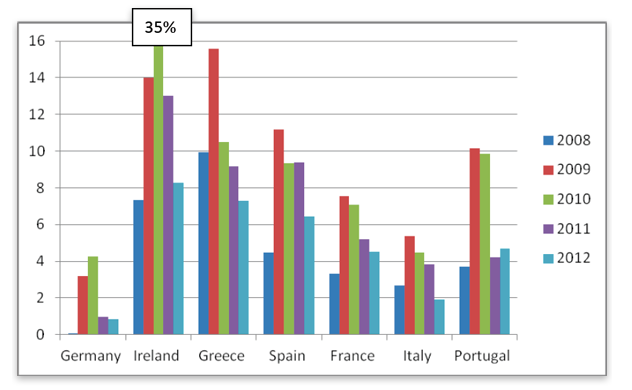

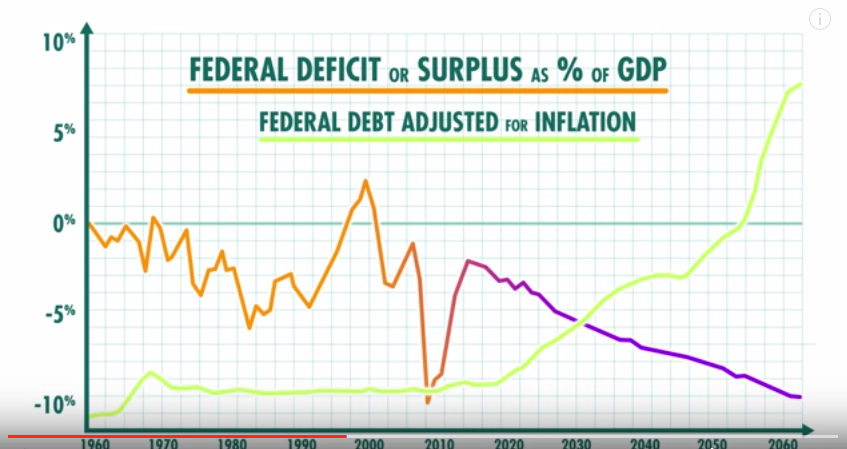

Crash Course opens the episode by defining the terms debt and deficit, and explaining how the United States has the largest debt of any country, but the US debt as a percentage of GDP is not as high as a few other countries whose economies are doing fine, namely Japan. However, the major concern isn’t the current size of the debt, but the growing deficit.

Most economists are not worried about the borrowing that the US has done already, because they are too worries about the borrowing they’re going to do.

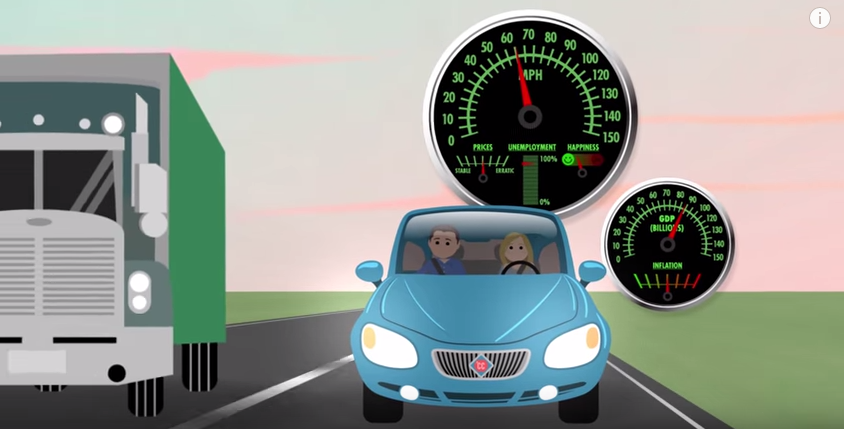

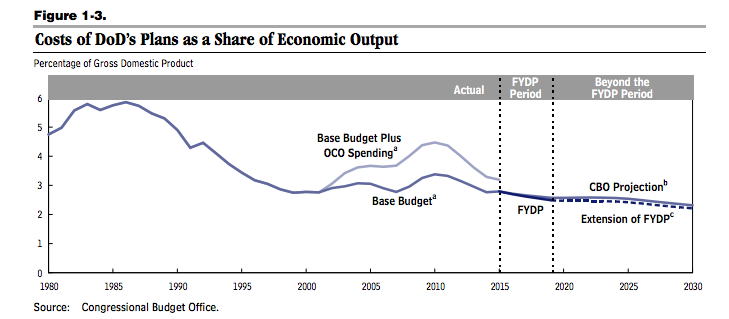

This is true, and as shown in the graph above, the US deficit is scheduled to increase through in future decades as government spending increases.

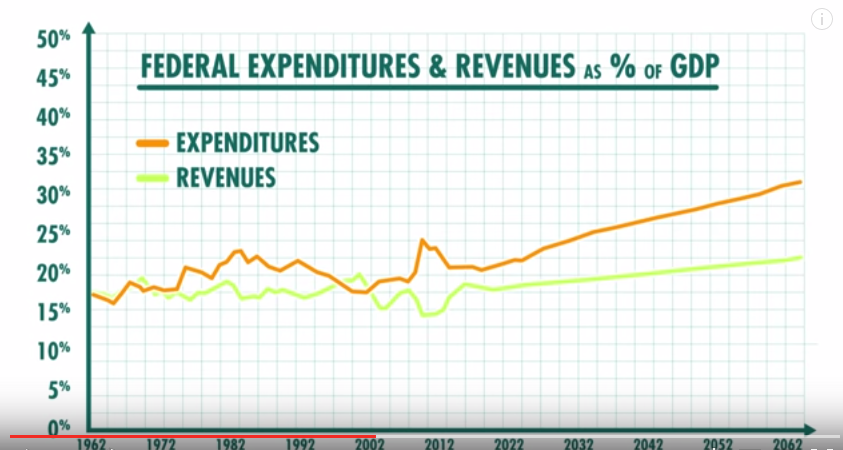

In the “too much spending vs. not enough revenue” argument, Crash Course shows that revenue (i.e. taxes, fees, tariffs, etc.) is set to increase (as a percentage of GDP) in the coming decades, so this is “not the problem”. While this is a subjective political argument (socialists and progressives might say that taxes are not high enough), we’ll assume that what she meant was that the increasing deficit is caused by increasing government spending, not decreasing revenue.

To de-politicize the spending issue, our co-host Adriene gives her explanation of which side is right when it comes to the question of “Where is there too much spending?”:

Let’s look at where the government actually spends its money. Conservatives might complain “It’s obvious! Handouts!” Liberals will say “It’s obvious! Defense!” Well, they’re both wrong. So who’s the biggest recipient of federal dollars?

Grandma and Grandpa. The government spends about a quarter of the budget on Social Security, and another quarter on healthcare programs. A lot of that goes to retired people on Medicare. They deserve it! They worked hard. And those are the programs that are expected to grow as baby boomers retire and live longer. Defense and other discretionary programs are actually projected to shrink slightly as a percentage of GDP.

First, let’s ignore the out-of-place and opinionated commentary of “they deserve it! They worked hard.”

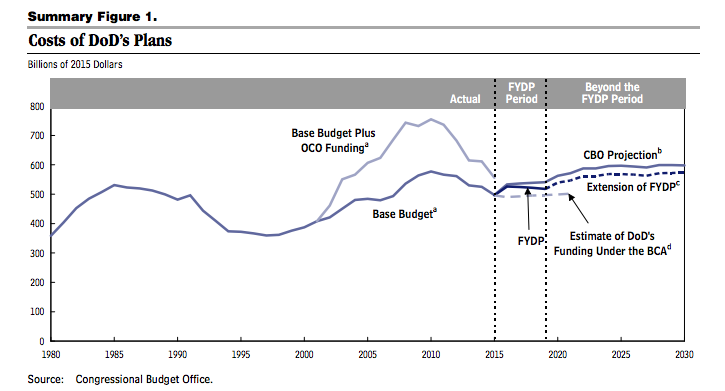

Second, while retirement spending is scheduled to increase significantly, so is defense.

The graph above shows the nominal costs of the Department of Defense. Until about 2022, there is an increase in spending. After that, it will stay at about 600 billion per year.

However, Adriene is right that Defense will shrink as a percentage of GDP, as you can see in the graph above. So if we’re looking at the cause of the increase in the deficit, as opposed to the already large deficit/debt or spending in general, she is correct.

Also, if tax-funded healthcare for the elderly is one of the leading causes of the increasing deficit, are conservatives actually wrong when they complain about “handouts”? I understand that Crash Course tries to remain politically neutral, but if the argument is between handouts vs. defense being the cause of a rising deficit, and you explain that Medicare is a primary cause, conservatives (in this case) are not wrong.

Also, in the liberals vs. conservatives argument, rarely have I heard the argument phrased within the context of defecit as percentage of GDP. Liberals are usually arguing that there is and has been too much defense spending generally, and conservatives argue against handouts being such a large part of the budget generally.

Debt and Borrowing

Our co-host Mr. Clifford explains how the US finances its debt:

First, to borrow, you need lenders, people who have decided to save money and loan it out, rather than spend it on something else. But there is a finite amount of money that savers can lend, and most of that savings is borrowed by the private sector, which is consumer that take out car loans and businesses that pay for things like factories and computers.

When the government runs a budget deficit, it borrows from that same pool of savings. And if the government continues to borrow, many economists worry that there will be fewer loans available for businesses, and that will hurt the long-run growth of the economy.

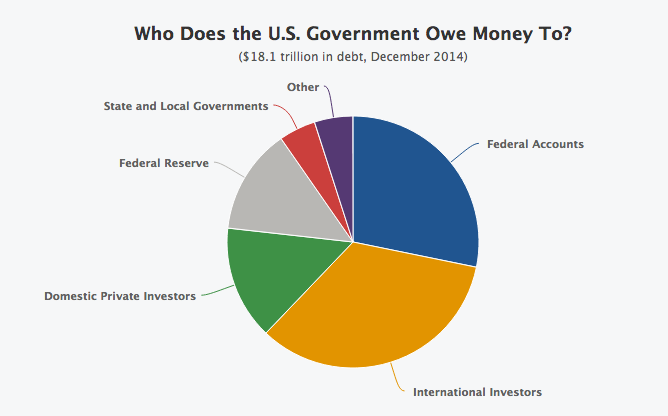

This is a huge misrepresentation of how government fuels its debt. Here is a graph that accurately shows who hold the government debt:

As you can see, domestic private investors, like what Mr. Clifford was talking about, account for less than 15% of government debt. The largest portion (34%) comes from international investors, which could be foreign governments or foreign citizens who are lending money to the US government and hoping to be paid back when the bond matures.

Federal Accounts accounts for 28%. This is where the government essentially borrows money from itself. Since different departments have different budgets, and some don’t necessarily need to spend it this year (for example, the budget that holds the Social Security deposits you’ve contributing to and hoping to get back eventually), other departments can borrow from those accounts and promise to pay it back later.

The Federal Reserve accounts for 14% of the debt. This is when the government creates money with a push of a button and buys treasury bonds (which is what you get when you loan money to the government). When the loans matures, the money is then just put into the treasury.

This is a big misrepresentation by Crash Course, and I was very surprised that they described US debt holders as only domestic lenders. How did this script get through production without someone saying “maybe we should say that this is only about 15% of debt, and there are many other ways the US finances its debt?”

We’ll pick back up with the rest of the video in Part 2. Stay tuned to see what Crash Course says about interest rates, and scenarios when spending might not get out of control.

Like what I wrote? Hate it? Drop some feedback in the comments. Also sign up for the Newsletter.