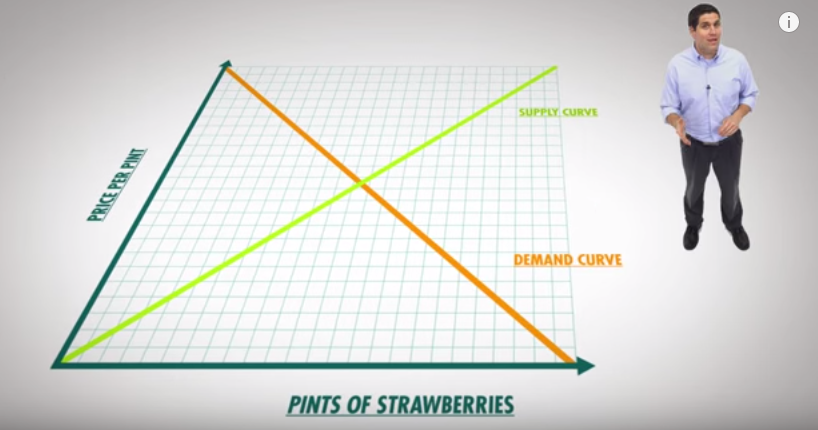

The Graph

Crash Course’s explanation of Supply and Demand is pretty spot on. Most economic schools (all but Marxism as far as I know) agree that the equilibrium price is reached where the demand and supply curves meet. The demand curve is determined by how much money buyers would be willing to pay for a product, and the supply curve is determined by how cheap of a price sellers would sell a product.

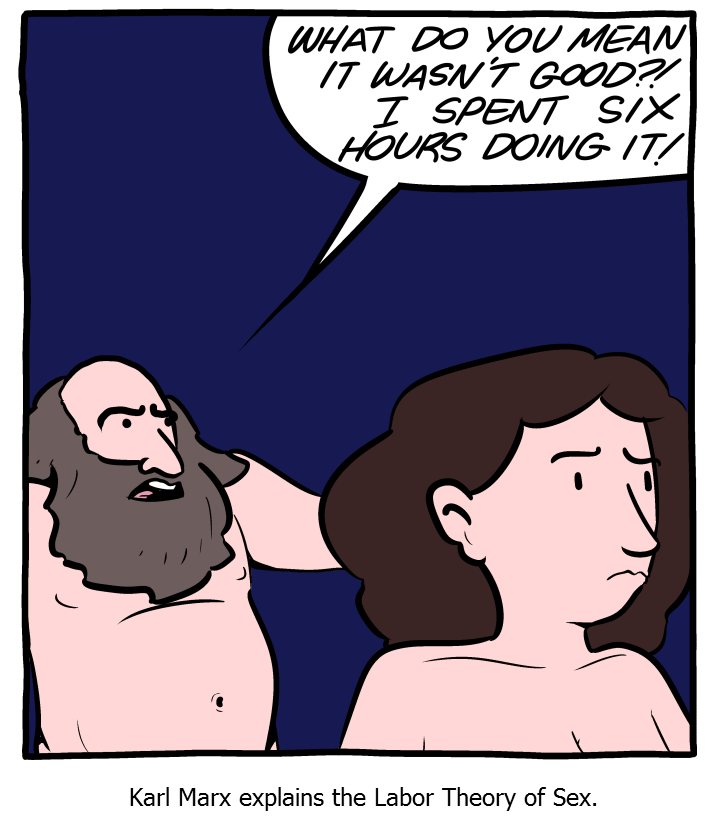

Marxists, however, believe in the Labor Theory of Value, and would probably reject the the graph entirely. The Labor Theory of Value states that a product’s value is determined by the amount of labor required to produce it, so if a product takes someone 1 hour to make and a different product takes 5 hours, then the second product must be more economically valuable.

(courtesy of SMBC Comics)

Government Subsidies

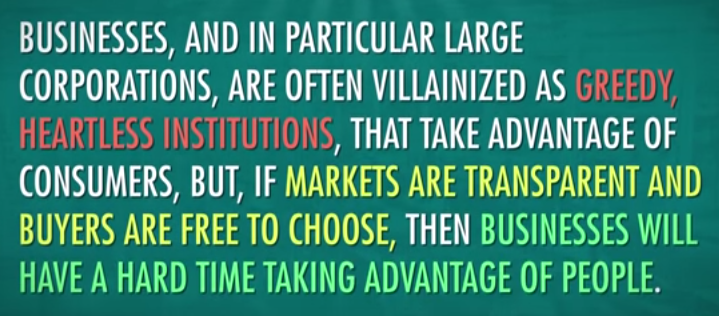

Crash Course notes correctly that the concept of “fairness” or “the right price” is subjective and is not based in economics:

Some people might want to talk about a price being fair or right, but that all depends on your point of view. The buyer always considers a low price to be a fair price, while the seller considers it unfair and vise versa. In general economists don’t really like to push opinions about prices. Voluntary exchange suggests that the price is there for a reason.

However, immediately after this, they input a little bit of their personal bias when they argue against government subsidies for business who are hurting because of low demand:

For example, assume the demand for strawberries inexplicably falls, so the demand curve shifts to the left, and the equilibrium price and quantity fall. Farmers might go to the government for assistance, but most economists argue there is no reason to bail them out. The market has spoken: strawberries are so over.

While I agree with their position, it’s little awkward to give a policy position immediately after saying that economists don’t like to push opinions. As I’ve noted previously, the market sometimes shifts jobs from one industry to another, and those who argue in favor of corporate subsidies are usually ones the who are afraid of having to change jobs.

But economists are correct in saying that the government should not bail out industries, because it would do a net harm to the population generally, even if it helps a sector. Crash Course acknowledges this when they say:

If the government helps the farmers by giving them a subsidy, it would be putting resources toward something that society doesn’t value. That would be inefficient.

Here I do wish Adriene would have mentioned what the most efficient way to use the resources would be: by not taking it from people in the first place. Since the market (i.e. people spending their own money freely) is the most efficient method of choosing what society wants, why do resources need to be taken from the market in the first place?

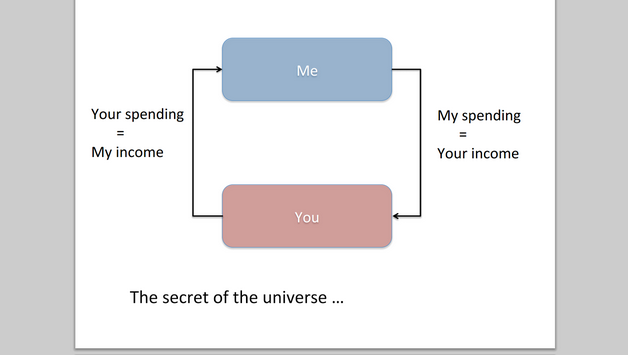

Where does the government get the money? Well, they get some of it from taxing households and businesses, and they get some of it from borrowing, but we’ll talk about that later.

Where does the government get the money? Well, they get some of it from taxing households and businesses, and they get some of it from borrowing, but we’ll talk about that later.