This week’s episode is a little better than last week’s. Crash Course does a good job of defining different kind of product markets out there, but could improve when talking about collusion and market substitutes. Let’s get started:

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Suppose Stan and I are arrested for scrawling in wet cement outside the YouTube studios. We’re being interviewed separately. If we both confess, we’ll both have to pay a $10,000 fine. If neither of us confesses, we’ll get off scot free. And If I take a deal and confess, but Stan doesn’t — I’ll walk away and Stan will owe $20,000. And vice versa.

This is not an appropriate example to show game theory. In game theory, the result of confessing when your accomplice doesn’t confess should be greater than if neither of you confess. If we were to tweak Crash Course’s example to make it work, if Adriene confessed and Stan didn’t, she would go free AND get $5000, making it a true dilemma between risking your freedom to get money. In Crash Course’s scenario as is, neither prisoner would confess, since there is no extra incentive.

This is particularly strange because Crash Course actually gives a perfect example of the prisoner’s dilemma later in the episode when talking about bread pricing, which we’ll get to later.

Pricing and Product Differentiation

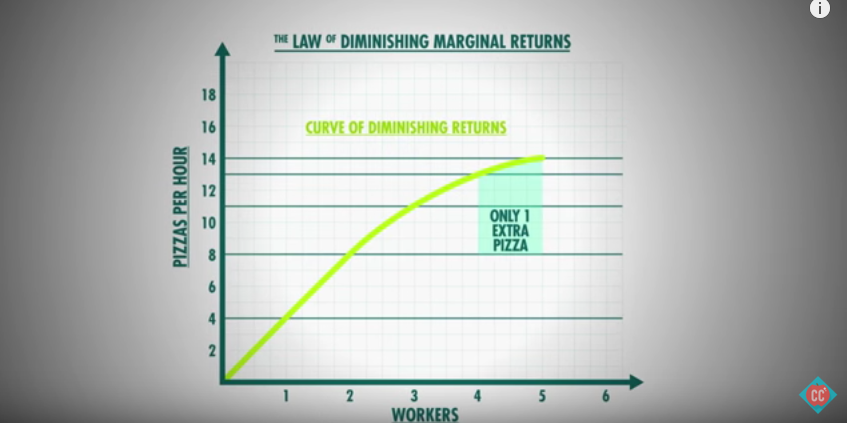

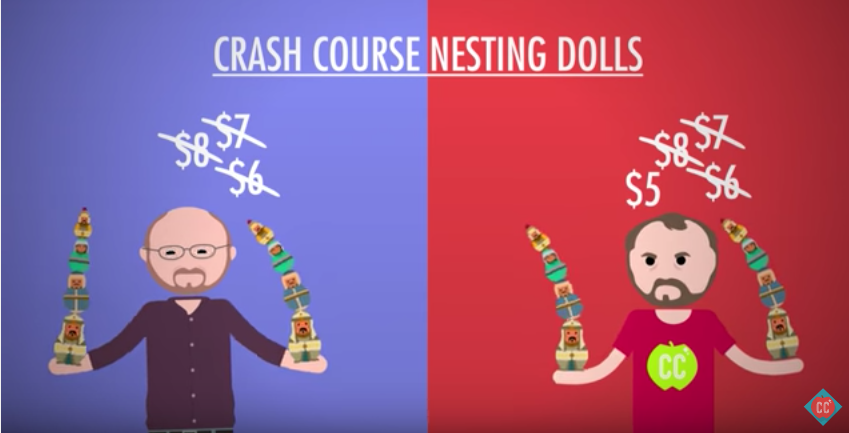

If Craig lowers his price on Crash Course nesting dolls, Phil will likely compete by dropping his prices as well. In the end they’re gonna continue to share customers equally, and earn less money.

If Craig understands game theory, he knows there’s no reason to change his price. Instead he focuses on providing knick-knacks that differentiate his kiosk from Phil’s. This can help explain why prices in oligopolies tend to get stuck and why companies focus so much on non-price competition.

Crash Course often talks about price as if its determined arbitrarily by whims of the entrepreneur. Businesses determine their price based on supply and demand, and are limited by a major factor: cost. If Craig and Phil are selling the exact same good, and Craig can afford to sell his good at a lower price while Phil cannot, Phil needs to sell a different good, which in the hypothetical, is exactly what Phil does.

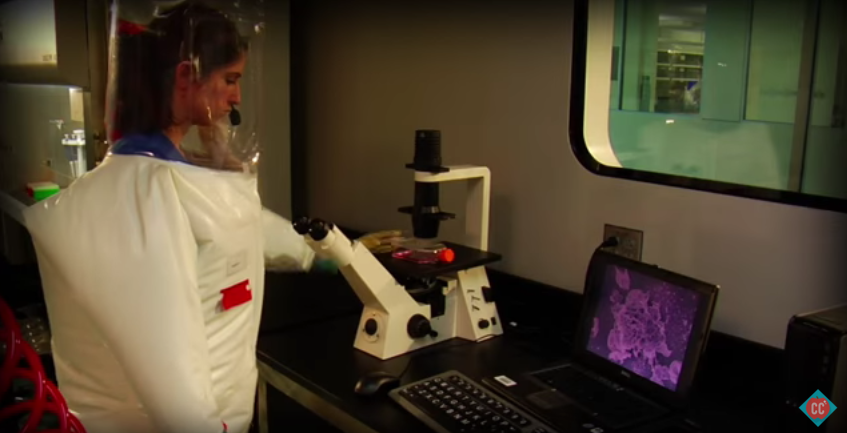

This is what Crash Course means when talking about non-price competition. Companies often distinguish themselves by portraying their product to be original and having no substitute. Think about how Apple markets the iPhone. For a lot of Apple users, Android would not give them the same comfort and familiarity, and they are willing to pay more because they feel that they are getting more. Android products give them a different (and to them, worse) experience that they won’t substitute for the iPhone.

Collusion

What if Craig and Phil don’t compete at all? What if instead, they agree to charge the same high price, conspiring to form what economists call a cartel? Again they split the customers 50/50, but now they make even more profit — benefiting at the expense of consumers. This is called collusion, and it’s illegal in the US. There are strict antitrust laws designed to prevent it. But that doesn’t mean companies don’t figure out other ways to raise prices.

Some economists argue that collusion would not occur in the free market, since it would not benefit the companies as Crash Course implies. Absent any government restrictions on entering the market, if all the companies agree to raise their prices together, it creates a greater incentive for a new competitor to enter the marketplace and charge a lower price. Those former market leaders might benefit in the short term (before the new competitor emerges), but they might not. People might buy substitutes if the price is too high.

Crash Course makes this exact point, although much later in the episode:

Even if they collude and agree to price high, they both have an incentive to cheat on that agreement. So collusion and cartels are often unstable. They can only last if the agreement is monitored and strictly enforced.

Price Leadership

Price leadership is when one company changes its prices, and its competitors have to decide if they’re going to follow suit. Since they’re not actively colluding, it’s technically legal. But it can be hard to tell the difference.

Look at airline baggage fees. When some airlines started charging fees for checked bags, other airlines quickly joined them. And when one big airline changes their baggage fee, the others tend move to the same price point. Are they colluding, or is this a case of price leadership? Well, the Justice Department’s looking into it.

Why would all of the airlines agree to raise their prices at once? Any potential gains in profit would likely be offset by the decline in the number of people priced out of the market. Does Crash Course think airlines arbitrarily chose luggage as their outlet for charging more for no reason? Could Crash Course give any other alternative explanation?

As we mentioned before, cost is a significant limitation in pricing. If one passenger is creating less cost for the airline, the airline would be able to give them a cheaper price. This is the case for luggage; it’s not that everyone with luggage has to pay more, but instead, airlines are separating the luggage cost from the ticket price, allowing some people to opt-out of paying for their luggage cost. Previously, luggage costs were priced into the ticket, making the overall ticket price higher. Do you recall which were the first airlines to charge for luggage? They were budget airlines like Spirit and Frontier, those who market the most towards having a low price.

Other countries’ laws differ, and cartels do exist. The best example is OPEC — The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. It’s an international cartel made up of 12 oil-producing countries that manipulate oil supplies to control prices. They control 80% of the world’s known oil reserves and nearly half of the world’s crude oil production.

OPEC collusively raises prices (and sometimes, lowers their prices) to their own peril. It takes longer for competitors and substitutes to enter the marketplace in energy markets, and OPEC may have benefitted at the outset, but the result was new competitors entering the markets (namely the fracking boom in the United States) as well as substitutes (more energy-efficient and electric cars were sold). OPEC’s artificially high prices hurt both the consumers and OPEC itself, but the market adjusted to better meet the needs of consumers.

How Businesses Compete

The highlight of the episode is when Crash Course gives a perfect example of why businesses are incentivized to charge the lowest price for their goods. As Crash Course explains, prices are determined by the predicted profit:

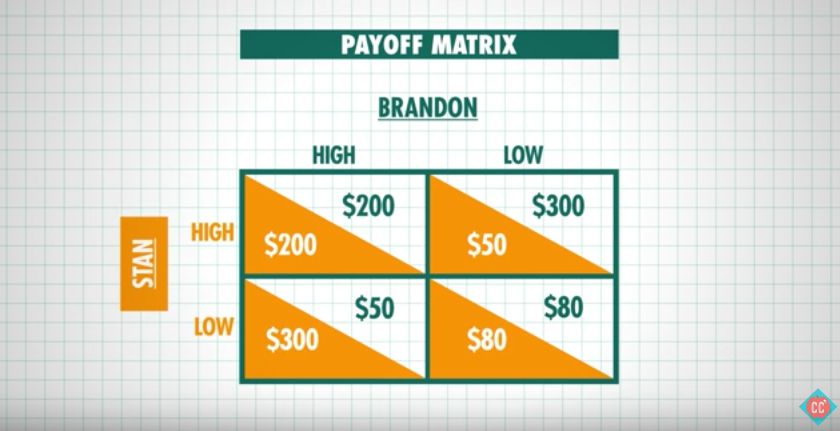

If Brandon prices high, Stan’s best response is to price low and if Brandon prices low than Stan’s best response is, again, to price low. That’s called having a dominant strategy: it always gives the best available outcome, no matter what the other guy does. For Brandon, pricing low is his dominant strategy too: regardless of what Stan does, pricing low always results in a better outcome.

Thanks for reading, and you can look forward to a new episode reviewed every Thursday! And don’t forget to join our newsletter and our facebook group, and comment below!