We have entered a new phase of Crash Course Economics and Crash Course Criticism. Episode 30 marks the first episode without one of our co-hosts, Mr. Clifford. If you recall, Mr. Clifford was a co-host most dedicated to “textbook economics,” while the other co-host, Adriene Hill, was more focused on practical application and real world examples of economics in action.

Last week in the episode 29, the hosts announced that it was “the end of their textbook economics episodes,” which means that now we are going to get involved with subjects only tangentially related to economics. Let’s see how the first one turned out:

After watching the first episode, it appears that this new phase of Crash Course Economics will deal more with the “how-to” of being an adult, and preparing the audience with some of the most challenging subjects of life. Despite still being called “Crash Course Economics,” there’s not much economics in this episode, but let’s do what we can.

Income vs. Age

In 2010, an upper income man in the US was expected to live to age 89. The same lower income man would live to 76. And this shortened lifespan has a big economic impact.

In effect, the rich receive a lot more government benefits over the course of their lives. That 89 year old upper-income man would collect an average of $522,000 dollars in government benefits during his life, while the lower-income man would only collect an average of $391,000 dollars.

This wouldn’t be a Crash Course episode without left-leaning commentary and unexplained statistics. Following this part of the episode, Crash Course moves to a completely new subject without tying these statistics together or explaining them, so we’ll try to do that here.

Disclaimer: I could not corroborate these numbers from my research. I tried to find where Crash Course got these figures, but I could not find them through Google, and they do not list them in the video description, so I’m just going to accept them as fact.

If rich people live longer, then they have more of an opportunity to reap the benefits of Social Security and Medicare, which generally start paying out in your 60’s. The longer you can stay alive past your mid-60’s, the more time you will have to receive a check every month from Social Security, and the more opportunities you will have to get health care, which is covered by Medicare.

It appears that the rich receive more in government benefits over the course of their lives because they live longer. If left at that, the viewer is to the think “What a rip off! The rich live longer and they take more from the government? After they complain so much about the poor taking so much in welfare?! The rich are the real welfare recipients!”

What’s not mentioned in this episode is a comparison to how much the rich contribute to taxes over the course of their lives. With this in mind, it no longer appears that the rich get the most out of these government programs, considering they pay much more than they receive. The lower income level of Americans, while they receive less in total benefits, likely contribute much less than they receive.

Old Age and the Economy

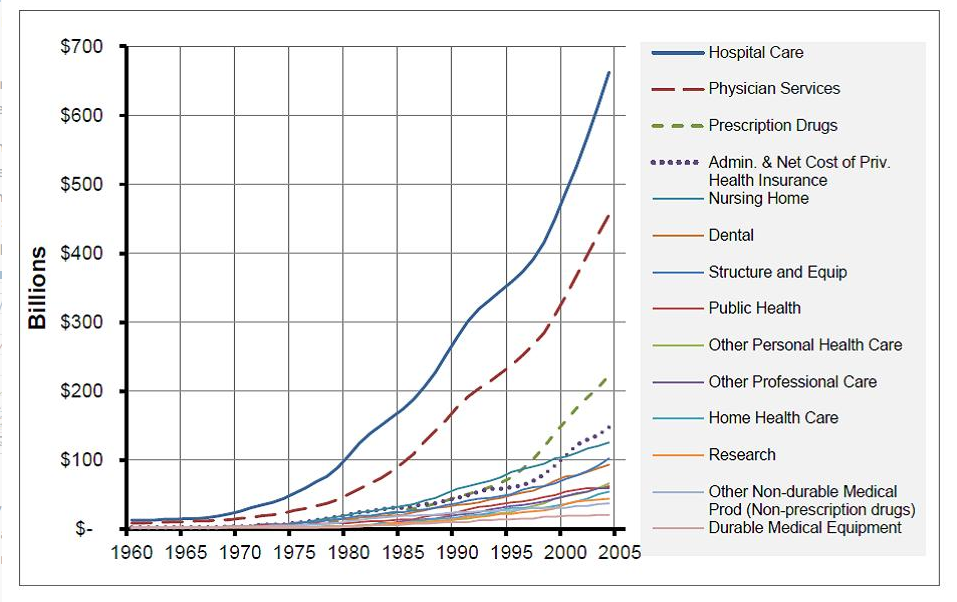

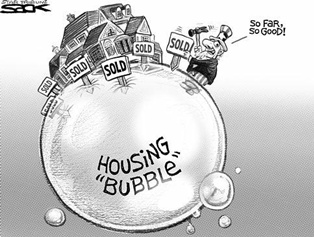

So how do our on average longer lives affect the economy? Well, economic thought about this stuff varies. Some economists argue that increased lifespans are, in a very basic sense, good for the economy. When people live longer, they have more years to consume stuff, contributing to economic growth. On the other hand, long life tends to come with more health problems, and memory-related illnesses have become much more prevalent[…]

Note: This is a very strange non sequitur. If the question was about how long lives affect the economy, why does Crash Course start talking about the personal struggles of growing older? What does this have to do with the economy in general?

Economically-speaking, the part in bold above shows a clear bias towards the Keynesian (or any spending-centric) Economic School of Thought. We talk about this a lot on Crash Course Criticism, so I won’t go into it again, but Spending (as opposed to Saving) does not necessarily benefit the economy.

But if it did, shouldn’t Crash Course say what a great benefit it is to the economy that the United States health care system is so expensive? That money would otherwise be stagnant in some old person’s bank account, but now it’s being spent!

However, it could still be argued that longer lives could improve the economy in a different way. With people living longer, each person would have more time to produce things for the economy, whether its by retiring at a later age or by taking up a new interest in retirement. In either scenario, stuff would get produced where it otherwise would not have happened.

Conclusion

This week’s post is on the short side, since (ironically) Crash Course Economics does not give a lot for an economist to analyze. The episode in general, however, seemed like a great opportunity to have the mostly young audience of Crash Course start thinking about a serious challenge in life, and despite the economic lacking and obvious political bias, the episode seemed to have very good message: plan for your own death. It’s a hard subject to think about, especially for Crash Course’s target audience, but doing it will save your family a lot of trouble.

Thanks for reading, and you can look forward to a new episode reviewed every Thursday! And don’t forget to join our newsletter and our facebook group, and comment below!