Crash Course’s episode this week (or rather, last week, I seem to be consistently a week behind) covers two subjects: Money and Finance. The episode is pretty much split down the middle between the two subjects. I thought their explanation of Finance was pretty accurate, while their explanation of money needs some clarification

Money

Technically, money is anything that’s used a medium of exchange.

This is a great move by Crash Course. While this may seem like an obvious statement to most, Crash Course could have taken a different approach, defining money as something only governments can certify. Their example of the use of cigarrettes (or pouches of mackerel) in prison prove that money can be anything, as long as people accept it.

The Bitcoin Question

Another form of digital money you often hear about it Bitcoin. Bitcoin is a virtual currency that is not issued or regulated by a specfic country, but since some people accept it as payment, many economists consider it money.

Crash Course could probably do a full episode on the question of whether Bitcoin can be considered a currency. They fall short of doing that here, instead opting for the “most economists…” line that Crash Course often uses in lieu of providing both sides of the argument.

Those who argue against Bitcoin being money aren’t just old curmudgeon economists who are resistant to new developments in technology. The argument against Bitcoin being money is that it contains no inherent value. In other words, cigarrettes can be smoked, mackerel can be eaten, gold can be worn as jewely, US dollars are the only thing you can legally use (or pay your taxes with) as money in the US. Bitcoin is not physical and cannot be used as anything other than a medium of exchange, so some people have problems with considering it money.

Before Crash Course makes you think that they like Bitcoin too much, they remind you that it’s associated with illegal activities:

Unlike other electronic currency, Bitcoin doesn’t involve a bank, so people can in theory buy things more anonymously. This appeals to people who don’t trust central banks and also people who want to buy illegal stuff online. That illegal trade means law enforcement and regulators are also very interested in Bitcoin.

No comment from Crash Course on what is the most popular money for illegal stuff offline (it’s the US Dollar).

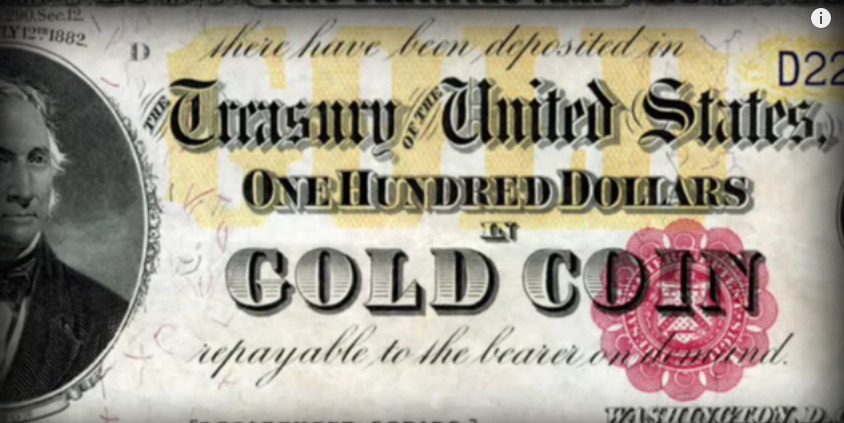

Gold

Did you notice something missing when Crash Course went through numerous historical examples of money?

Coins have been used for thousands of year, and they are a great example of money […] Animals like cattle and sheep, also stacks of grain, all these have been used as money. Some societies even used feathers or shells. The indiginous people on Yap Island in the Pacific Ocean used money called Rai Stone…

I found it strange that Crash Course did not want to mention that gold is the most consistent money throughout cultures and countries in history. Many of the coins in history were made of precious metals. I know that Crash Course wanted to go into the Gold Standard later in the video, but it seemed strange that they left gold out of the list of historical examples of money.

The Gold Standard

This is another topic worthy of its own video, and unfortuntely Crash Course quickly explained away arguments for the gold standard:

There is kind of a glaring question here: what makes these pieces of paper so valuable? Well, in the past each dollar issued by the US government was redeemable for a specific amount of gold. That was called the Gold Standard, and it meant that the government couldn’t issue more money than it had in gold reserves. Back in the 1930’s the US decided to move off the Gold Standard, and some people freaked out about not having something tangible to back our money, but it’s important to remember that money, whether it’s cash or gold or small pouches of mackerel, is all about confidence.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman once said “The pieces of green paper have value because everyone thinks they have value.” With that in mind, a gold standard, or even a Mackerel Standard, might not make money more valuable or reliable.

A lot of economists agree with this (!), which is why no country uses the Gold Standard.

Crash Course’s final argument against the Gold Standard here is that “it might not make money more valuable or reliable.” No talk about the benefits of going off the gold standard, just that the Gold Standard may or may be good. And by the way, most economists agree with this, so you should just accept it.

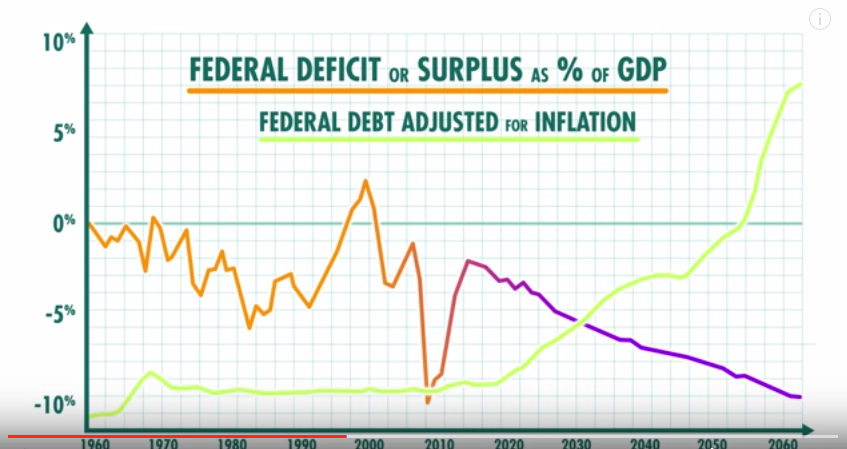

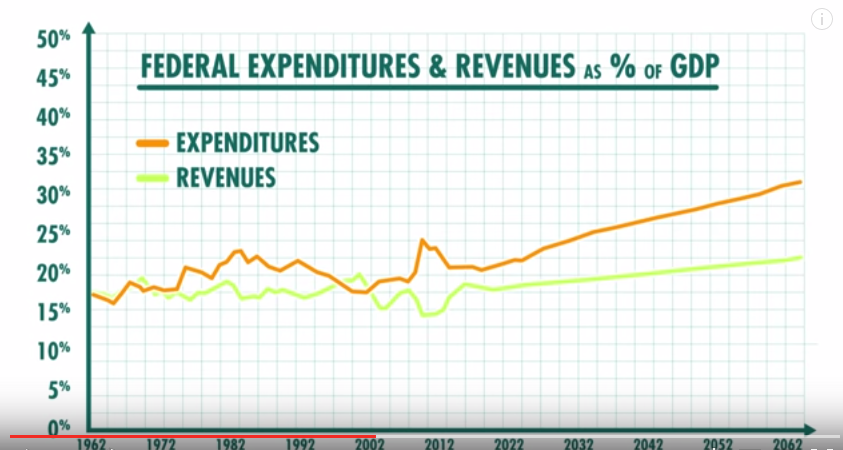

This is hardly an argument at all. The real argument for the gold standard goes back to what our co-host Mr. Clifford said earlier: “the government couldn’t issue more money than it had in gold reserves.”

Governments were fiscally constrained by the gold standard, since they couldn’t print money without backing it with gold (and you can’t just print gold like you can money). So in order to solve these government spending problems, the US went off the Gold Standard to allow the government to print and spend without much constraint.

Of course, as Mr. Clifford said, people were nervous about going off the gold standard. You’d expect people to exchange their dollars for gold in panic, but to protect against this, in 1933, all Americans were forced to give their gold to the government at an exchange rate determined by the government. The option of buying gold was not legally available to Americans until 1971.

A lot of economists agree with this, which is why no country uses the Gold Standard.

Countries do not implement policies because economists agree on them. In fact, there are a lot of things economists agree on government policy goes directly against. The real reason why no country is on the gold standard is because it allows governments to print and spend without restraint.

Finance

Not much in terms of criticism here. The second half of Crash Course’s video was pretty informative and unobjectionable, talking about how Loans, Bonds, Stocks, Equity, and Debt work. Compared to the first half of the video, this was a very solid explanation of finance.

While the explanation of these financial instruments aren’t economics per se, it is important to understand what all of these things mean, especially when talking about macroeconomic policy and next week’s subject, Economic Crises. Did you see anything objectionable in their section on Finance?

Like what I wrote? Hate it? Leave some feedback in the comments.