Crash Course’s second episode was pretty agreeable. It explained why free trade is mutually beneficial, gave a good explanation of the Production Possibilities Frontier, and it even knocked down common political arguments that are demonstrably false. Let’s start with their explanation of specialization.

Specialization is a Pizzeria?

Crash Course gives a visualization of specialization with the analogy of a pizza-making assembly line. I hope that this example is effective for those unfamiliar with specialization, but what I was thinking when I saw this was “couldn’t each of these guys very easily switch to a different position at the pizzeria without much fuss? Is the guy cutting vegetables really that much better at doing this task than anyone else?” I wasn’t sure if this example was advocating for specialization or just an assembly line business model.

Crash Course gives a visualization of specialization with the analogy of a pizza-making assembly line. I hope that this example is effective for those unfamiliar with specialization, but what I was thinking when I saw this was “couldn’t each of these guys very easily switch to a different position at the pizzeria without much fuss? Is the guy cutting vegetables really that much better at doing this task than anyone else?” I wasn’t sure if this example was advocating for specialization or just an assembly line business model.

Their best example comes from showing what one person would have to do to make a pizza by himself. This is a modern take on Leonard Read’s I, Pencil, and it gets the point across faster even than it would take you to read Read’s short essay.

National Trade

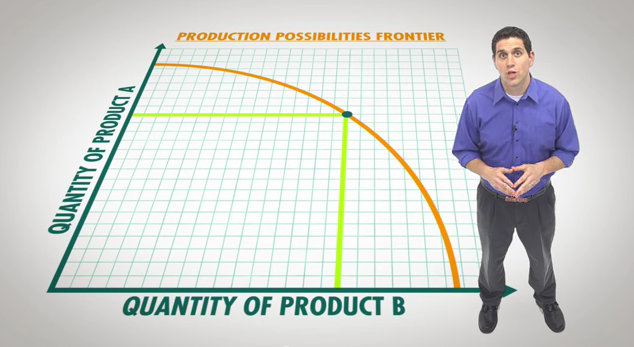

Understanding the Production Possibilities Frontier is challenging. They explained the model quickly, and although I was able to follow along in real time, I needed to pause the video after this segment to visualize and absorb the lesson again in my head.

Their conclusion from the model was direct:

You might hear a politician or someone on the news argue that international trade destroys domestic jobs, and even though it may seem counterintuitive, economists for centuries have argued that trade is mutually beneficial to whoever is trading.

To be fair though, international trade may destroy particular domestic jobs, but not the total number of jobs. In Crash Course’s example, the American shoe industry would suffer as a result of free trade, and the airplane industry would grow. People hate making less money or getting laid off, even if you explain to them that the economy is better off for it. Just ask the cab industry.

Let’s go back to that final line: trade is mutually beneficial to whoever is trading. While true, it’s important to compare this statement to the opposite argument: trade is a zero-sum game where one party wins and the other loses.

There are a fair amount of people who believe that as people get rich, these people are necessarily making others poorer (the money has to come from somewhere right?). With the exception of thieves, who actually do increase their wealth at the expense of someone else’s wealth, people get rich because a lot of other people have wanted to trade with them. Bill Gates is not rich because people are poor, he’s rich because a lot of people value his products more than holding on to cash.

The episode gave two good examples of the national benefits of free trade: Japan and Taiwan. While these examples are good, Japan and Taiwan also have a fair amount of natural resources, and Japan has historically been a developed country. Instead of these examples, I would look at Hong Kong and Singapore. These countries are closer to the size of a city, with very few natural resources, and just 60 years ago would be considered poor underdeveloped countries. But from decades of free trade policies (they are currently #1 and #2 most economically free countries in the world), these tiny countries now have a greater GDP per capita than the European Union’s average.

Not much objection in this week’s episode, and we even have a teaser of next week:

Next time we’ll show you how some of these ideas get turned into economic systems, and how these systems contribute to differences between countries.