For episode 3, Crash Course is going big. This episode talks about different macroeconomic systems and the proper role of government, all in 10 minutes. There are a lot of things to unpack in this episode, so this review will consist of multiple parts.

The Factors of Production

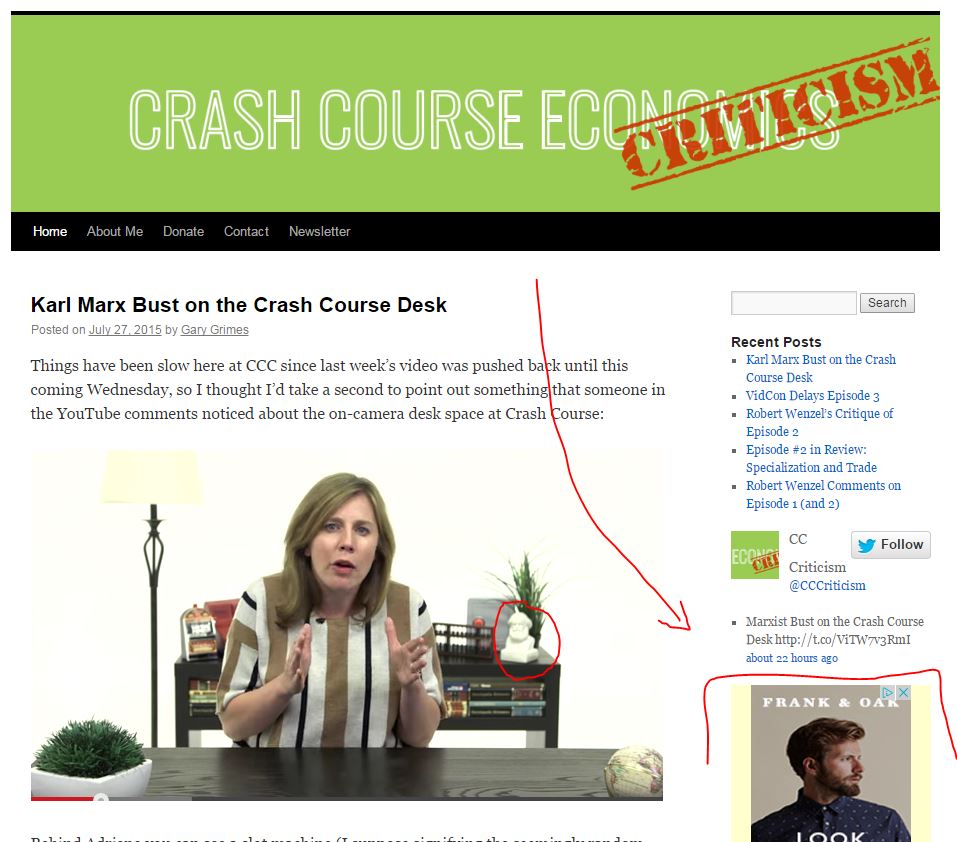

There is no better introduction to macroeconomic theory than by talking about control over the factors of production. Although the term was originated and defined by Adam Smith, Crash Course decided to quote Karl Marx for the same definition: Land, Labor, and Capital.

Free Marketeers might be upset that they attributed it to Marx, but it makes sense. Communists (and socialists for the most part) are often the ones who use the phrase “Factors/Means of Production,” and if you hear someone mention it in conversation, it’s more likely that they are a Marxist than a devotee of Adam Smith.

A Planned Economy

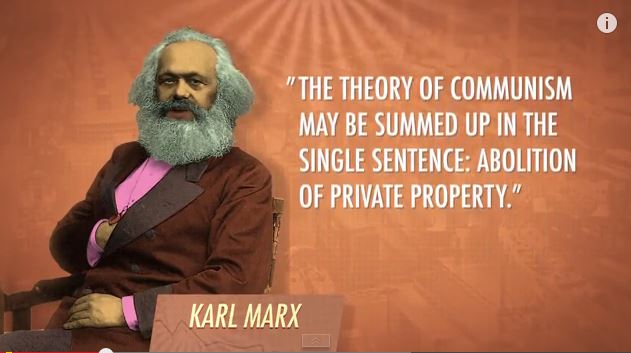

I got confused with Crash Course’s definition of a fully planned economy and its relation to Communism:

In a planned economy, the government controls the factors of production, and it’s easy to assume that that’s the same thing as communism or socialism, but that’s not quite right. According to Karl Marx, “The theory of Communism may be summed up in the single sentence: abolition of private property.”

If the State owns all factors of production, and therefore owns all property produced from those factors of production, doesn’t that automatically eliminate private property? In other words, how does the public control over the means of production not create communism? What else could it be?

In fact, according to the Wikipedia entry on Communism, Communism is defined by the common ownership of the means of production. There is not a mention of private property in this definition because the absence of private property is the logical conclusion from the definition.

(However, I would accept that Marx’s Communist society is stateless, so Mr. Clifford’s mention of a government controlling the means of production would not be Communism)

A Free Market Economy

Crash Course gave an excellent definition of a free market economy:

In Free Market or Capitalist Economies, individuals own the factors of production, and the government keeps its nose out of this stuff and adopts a Laissez Faire or hands-off approach to production, commerce and trade.

This is, in my opinion, Crash Course’s best work yet. They continue:

In Free Market Economies, businesses make things like cars, not to do good for mankind, but because they want to make a profit. Since consumers, that’s me and you, get to choose which car we want, car producers need to make a car with the right features at the right price. Economists call this the invisible hand.

This is a great definition of capitalism, and one that emphasizes the consumers’ essential role in the process. Instead of focusing on a business’s desire for profit (a necessary element, but not what drives market successes and failures), consumers determine the market winners through their own preferences:

Scarce resources will go to the most desired use and they’ll be used efficiently, more or less. After all if a business is wasteful or inefficient, or makes something that no one wants to buy, then some other business will make a similar product that is either better or cheaper or both. If there’s no consumer demand for a product, resources wont be wasted producing it.

Businesses could not survive in a free market if they did not provide customers with what they wanted better than the competition. Crash Course also provides a look at the alternative: a centrally planned economy for consumer goods:

Assume instead that a government agency was in charge of deciding exactly which types of cars and cell phones and shoes to make. Do you think they could quickly respond to changes in tastes and preferences? If there was only one government monopoly producing cars, do you think they would be produced efficiently?

We don’t even need to speculate what this would be like because it has already happened. For example, during the Soviet Occupation in East Germany, automotive manufacturer VEB Sachsenring had a government-created monopoly on automobile production. Their product was the Trabant, the only car available to East Germans, and often considered one of the worst cars ever built. On top of this, due to the mismanagement of the factors of production, the waiting list for one of these cars was ten years.

Is there anything that the government must do because free markets won’t? Come back later for Part 2.